| The Ruthless Richard Ratcliffe Founder of the Town of Providence (now Fairfax City) |

|

by Debbie Robison January 29, 2019 |

| THE SCHEME |

Original Portion of Fairfax County Courthouse, Built 1800 Richard Ratcliffe had an audacious scheme for how he could make a lot of money. His plan was to donate land for the Fairfax County courthouse and create his own private town that would exploit the need citizens had to visit the courthouse to transact business. His ultimate goal: a monopoly on the tavern and livery stable trades. Ratcliffe knew that towns created around a courthouse flourished, so when the County of Fairfax required a new location for a courthouse, he convinced the justices of the court to accept an offer of donated land. Ratcliffe was well known to the justices of the court. In fact, he was one himself. |

| THE REAL REASON FOR MOVING THE COURT |

Petition to Remove Courthouse from Alexandria, Petition Courtesy Library of Virginia Ratcliffe was one of 550 inhabitants of Fairfax County, primarily gentlemen and farmers residing outside of the Town of Alexandria, who petitioned the Virginia General Assembly in 1789 to construct a new courthouse and jail in the center of the county. Their argument for the move was not just that a central location would be more convenient, but that the inconvenience of traveling to Alexandria to attend court resulted in cases being decided by a different class of people: town residents rather than farmers. They argued that their cases were decided by notorious and unfit Town Judges and by juries composed of foreigners and strangers unacquainted with the laws, customs, and institutions of the Commonwealth of Virginia, or the rights of the people. [1] The Virginia General Assembly passed an act to alter the place for holding court to be within one mile of the crossroads at Price’s Ordinary (the intersection of present-day Braddock Road and Backlick Road), but an acceptable location couldn’t be found.[2] Either there wasn’t a good source of water or the expense of moving the public roads to the site was too great. [3] Once it was known that the Town of Alexandria would be annexed as part of the District of Columbia, the townsmen and farmers no longer had competing interests in where the court would be located. [4] The court had to move out of Alexandria and the townsmen no longer had a say in the location. |

| THE DECISION TO CHOOSE RATCLIFFE’S LAND FOR THE COURTHOUSE |

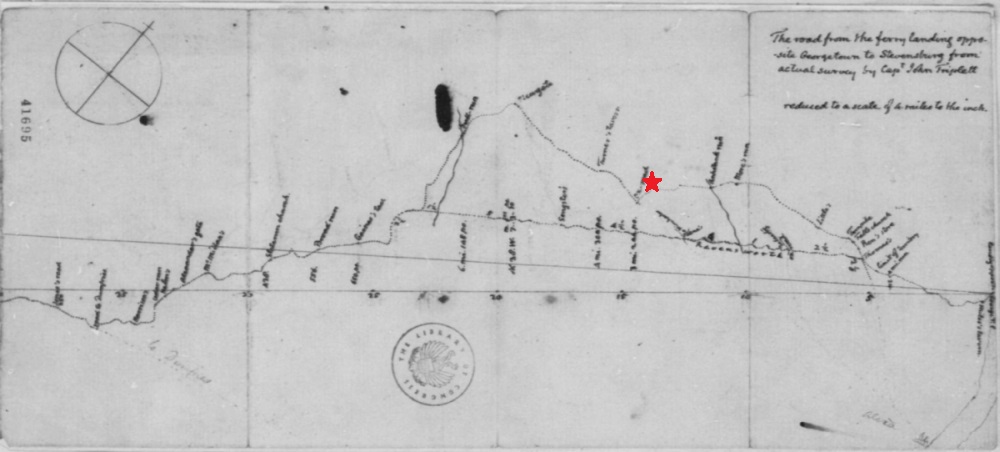

Map of Route from Georgetown to Stevensburg, ca 1791, by Capt. John Triplett, Star Indicates Approximate Future Town Site, Image Courtesy Library of Congress, Click on Map for Larger Image (Original quality not high)

×

Concurrent with the need to relocate the Fairfax courthouse out of Alexandria, the inhabitants of eastern Loudoun County found it difficult, due to distance and stream crossings, to travel to the courthouse in Leesburg and desired a change in the county boundary so they would be included in Fairfax County. [5] When the Virginia General Assembly enacted an act to move the county line from Difficult Run to the present boundary line, the center of the county shifted west. [6] In 1798, the justices of the Fairfax County court approved a new county line and agreed that a central location for the new courthouse and other public buildings would be on Richard Ratcliffe’s land somewhere near a spot that the justices determined, based solely on a map, was the most eligible place. Ratcliffe was present for the discussion and agreed to donate at least four acres for the public buildings. [7] The location was determined before viewing the land to see if it was suitable. Commissioners were appointed to go out and find a proper place on Ratcliffe’s land, and the following month they returned to court with a survey of four acres near Caleb Earp’s store. Although the land wasn’t on a major east-west route (the Little River Turnpike wasn’t built yet), it was on a road that connected Stevensburg, near Culpeper, to Georgetown. [8]

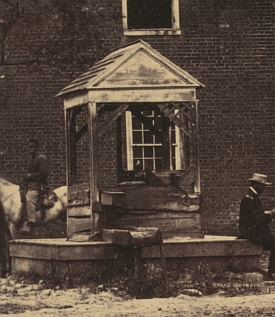

Well at Fairfax County Courthouse, 1863, Photographer Timothy O'Sullivan, Image Courtesy Library of Congress There must have been some concern over the lack of springs on the property, because Ratcliffe had to agree to allow the public free access to all of his springs on all of his land and to dig a well on the courthouse property. [9] Recall that nine years earlier, lack of springs was cause enough to reject sites for the courthouse. |

| THE PRIVATE TOWN |

|

By the time the courthouse was in use in April 1800, Ratcliffe had just finished constructing a two-story brick tavern on an adjacent lot. [10] His son, John Ratcliffe, received a license to operate the tavern on the first day that court was held in the new courthouse. [11] The tavern, measuring 44’x32’, was supported by a kitchen building, smoke house, and stables. [12] In November 1800, Ratcliffe began promoting his scheme for a private town; i.e. one not created by an act of the Virginia General Assembly. He advertised the brick tavern and a store for rent and offered to rent a few lots, suggesting that the place was suitable for a saddler, blacksmith, wheelwright, tanner, shoemaker, etc. [13] He did not offer to sell any lots. Ratcliffe worked to stifle any competition. He owned all of the land surrounding the courthouse, but had donated the courthouse grounds to the County. In order to ensure that he didn’t lose any business, he made a motion at the court that sutlers and retailers of liquor could not set up booths on the public lot. Ratcliffe’s fellow justices agreed, and the sheriff was ordered to give notice.[14] The following year, Charles Hughes and Edward Tucker began operating Ratcliffe’s tavern. They also rented the adjoining store, possibly the one previously occupied by Caleb Earp, and a smith’s shop where Tucker would carry on the gun smith business. They particularly wished to attract drovers to the tavern, and advertised that good grazing was available for any number of cattle. [15] Apparently, Richard Ratcliffe used his influence to route the Little River Turnpike past his tavern. The debate was raging in 1803: should the turnpike follow an existing road (present-day Braddock Road) and pass through Centreville, or go past the courthouse. One man in favor of the Centreville route didn’t hesitate to mention in a newspaper editorial that the accommodation of this or that man’s tavern at the Court-House or elsewhere ought to be totally out of the question. Clearly, he was referring to Ratcliffe, since Ratcliffe was the only man with at tavern at the courthouse. The editorial went on to say that the courthouse route would have been the last route ever contemplated if no tavern and court-house had been there. [16] In the end, the decision was made to route the turnpike past the courthouse. And who was the contractor hired to build the turnpike?... Richard Ratcliffe. |

| THE TRICK RATCLIFFE PLAYED |

|

By 1804, people in Fairfax County, Alexandria, and the City of Washington had enough of Ratcliffe’s monopoly on the land surrounding the courthouse. Eighty-eight men signed a petition asking that 15 to 20 acres at the courthouse be condemned by the Commonwealth of Virginia and laid out into a town under appropriate and necessary regulations and restrictions. The petitioners argued that there was only one tavern (badly kept) at the courthouse, which was insufficient for the number of people transacting business at the courthouse or traveling on major roads that passed the courthouse. They complained about Ratcliffe’s motion to exclude other tavern keepers from selling liquor, beer, and cakes on the courthouse grounds. In fact, Ratcliffe had been making speeches stating that the deed he executed to the courthouse commissioners gave him exclusive right and benefit in the lot and that no other use could be made of it except for holding court. [17] William Moss, clerk of the court, circulated the petition. He had been obliged to pay board at Ratcliffe’s tavern for himself and his assistants, and still had to live in a disagreeable manner. He frequently applied to Ratcliffe to purchase a lot, but Ratcliffe either evaded the question or outright refused. [18] Ratcliffe learned about the petition and submitted his own, asking that a town be created on 14 acres or more of his land. Ratcliffe submitted a proposed town plat, which indicated the location of existing buildings consisting of the courthouse, a tavern with kitchen and stables, a storehouse with kitchen and shop, and a tannery with a dwelling house, bark house, and tanyard. [19] You may think Ratcliffe’s petition runs contrary to his desire to have a monopoly on the tavern and livery stable trades, but Ratcliffe had a plan. And Moss knew about it. Moss heard Ratcliffe say there never should be a Town established as long as a drop of blood remains in his veins, that if a Law was obtained, he as the proprietor, would purchase up all the Lotts, and in case of a forfeiture, he would procure a friend to do it, and in that manner defeat the Law. [20] The Virginia General Assembly passed an act on January 14, 1805 creating the Town of Providence, a name suggested by Ratcliffe. The act appointed town trustees who would advertise lots for sale, except for the one-acre tavern lot that would remain owned by Ratcliffe and the four-acre courthouse lot. Those who bought lots were required to build a dwelling house on the lot at least 16 feet square with a brick or stone chimney finished for habitation within seven years of the sale. The money paid for the lots would be distributed to Richard Ratcliffe, the original owner of the land.

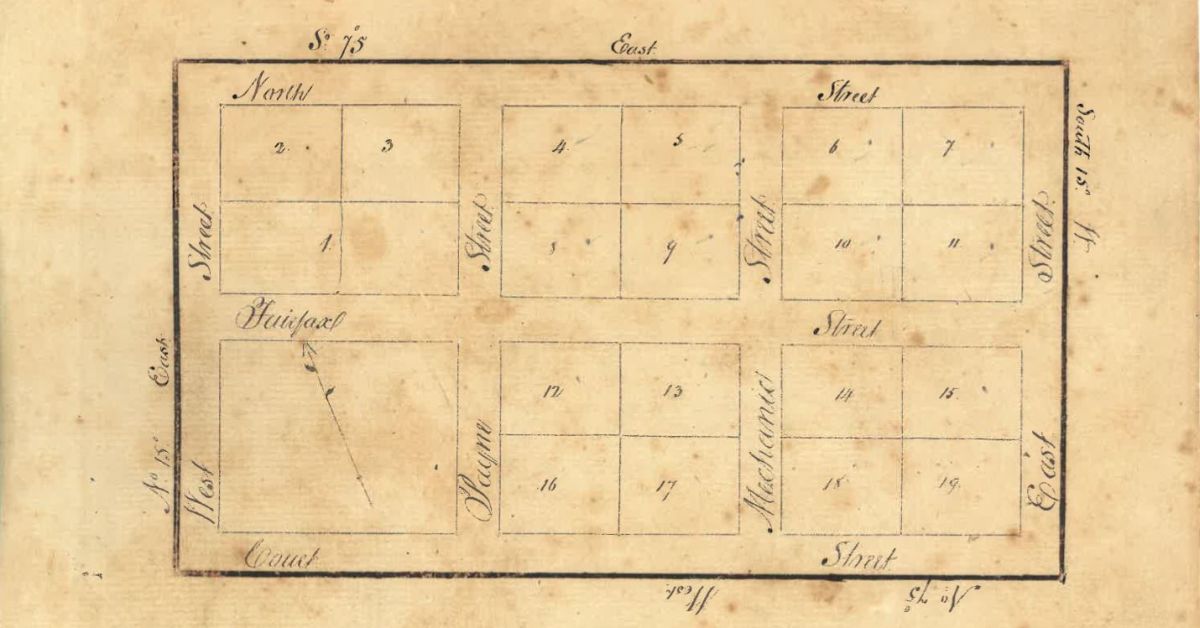

Plat of the Town of Providence, 1811, by Robert Ratcliffe, An important provision of the act was that no one person could purchase, directly or indirectly, more than one half of the lots in the town. If any person should, contrary to the intent of the act, either in person or by agent, purchase a greater number of lots than permitted, the lots would revert to the town trustees for sale and the funds applied to the betterment of the town. [21] Town trustees proceeded to advertise the lots for sale beginning in July 1805. [22] The auction was held on the 22nd and 23rd of October. Every lot was sold. Richard Ratcliffe purchased one half of the lots and the other lots were purchased by Stephen Daniel, Spencer Jackson, Robert Ratcliffe, and John Ratcliffe.[23] In other words, all of the lots were purchased by Richard Ratcliffe, his sons, and his sons-in-law. Possibly due to the law’s intent being disregarded, the town trustees did not give the purchasers deeds to the lots. This remained true for six years until Ratcliffe obtained another Act from the Virginia General Assembly to obtain a deed for all of the lots. [24] |

| THE MONOPOLY |

|

Having held onto all of the lots, Ratcliffe began to develop his rental properties. In most cases, he built houses on lots and entered into rental agreements with tenants, though how much effort and money he expended on maintaining the properties is questionable. On two lots, he built log grog shops, as one person called them. More a place to have a pint than to stay for the night.

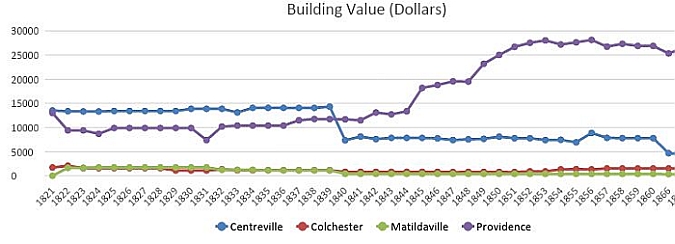

Town Plat Over 1937 Aerial Photo, Showing Courthouse Lot in Green and Racecourse in Magenta, Background Image Courtesy US Department of Agriculture and Fairfax County In 1810, John Maddox agreed to rent the brick tavern for a large annual sum on the condition that Ratcliffe would put the tavern in good condition by 1811, construct sheds for carriages and horses, enclose one acre around the tavern for use as a garden, and build an ice house. Ratcliffe also agreed to enclose three or four acres for a pasture. A court case ensued when John Maddox attempted to reduce his past due rent payments by arguing that Ratcliffe hindered the success of his business; first by not making the necessary repairs, second by building a competing brick tavern on the pasture lot leased to Maddox, and lastly, by taking business away from the racecourse Maddox built. Based on depositions, it appears that prior to the September 1812 races, Ratcliffe had slaves, superintended by Samuel Ratcliffe, enter onto the racecourse grounds and remove thick shrubs that were blocking the view of the race from his other lots. Ratcliffe then collected fees from sutlers who rented booths on Racliffe's lots instead of the racecourse land. Price Skinner, who had a tavern license and may have operated one of the grog shops on one of Ratcliffe's lots, was accused of entering onto Maddox's racefield and selling liquor and toddys to the race judges, thereby taking the business away from Maddox. The following year, Maddox relocated the racecourse to Capt. John Wren’s land nearby. True to form, Ratcliffe threatened Mr. Wren, stating that if he allowed races to be run on his field again, Ratcliffe would throw down Wren's fences, which Mr. Wren swore Ratcliffe did for several sections of fence at different times, including at the beginning of the June 1813 races. Prior to the June 1814 races, Ratcliffe built a road down the border between his land and Wrens, removing some of Wrens fencing in the process,and encouraged visitors to the race to enter onto his land, thus avoiding the race tollbooth. Sutlers also set up booths on Ratcliffe's land, including Price Skinner who attempted to rent a booth from Maddox, but found the rent to be too high. [25] Ratcliffe was determined to have a monopoly. He refused to sell any lot without a stipulation in the deed that no tavern or livery stable could be built on the lot. Unfortunately for Ratcliffe, he forgot to include this provision in James Allison’s sales contract for part of lot 8. James Allison and his brother Gordon Allison lived in a house on the lot and operated a store there. They sold liquor and crackers at the store in small quantities, which some people drank and ate on the porch, much to Ratcliffe’s displeasure. Ratcliffe wanted all liquor and food sales to benefit his taverns. When the Allisons began constructing another building on the lot for use as a tavern, and requested a deed, Ratcliffe refused. Allison took Ratcliffe to court and won. [26] The only other lot in the Town of Providence that Ratcliffe sold during his lifetime was the lot where the existing Ratcliffe-Allison house is located. [27] Even the existing Draper House was a rental property. Ratcliffe’s monopoly stifled investment at the courthouse and kept a lid on development. It wasn’t until Ratcliffe’s death and his heirs sold lots in the mid-1840s that town development flourished. The following chart compares the total building value on all town lots each year. It is evident that the building values remained fairly consistent during Ratcliffes lifetime. Once his heirs started selling lots, others made investments in houses in the town. Several existing historic buildings in the town were constructed during this period. [28]

Comparison of Town Building Values Based on Land Tax Assessments [1] Inhabitants Petition, 03 Nov 1789, Fairfax County, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [2] “An Act for altering the place of holding courts in the county of Fairfax,” Hening Statutes, Laws of Virginia, Vol. 13, October 1789 – 14th year of Commonwealth, p. 79, as viewed at http://vagenweb.org/hening/vol13-04.htm#page_79. [3] Fairfax County Court Order Book, Part 2 1788-1792, 18 May 1790, p. 292. [4] “An act to amend 'An Act for Establishing the Temporary and Permanent Seat of the Government of the United States,” March 3, 1791, A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.db&recNum=337 [5] Inhabitants of Fairfax and Loudoun Legislative Petition, 11 Dec 1797, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [6] “An ACT for adding part of the county of Loudoun to the county of Fairfax, and altering the place for holding courts in Fairfax county,” Virginia. The Statutes At Large of Virginia: From October Session 1792, to December Session 1906 [i.e. 1807], Inclusive, In Three Volumes, (new Series,) Being a Continuation of Hening .... Richmond: Printed by S. Shepherd, 183536, Chap. 37, p. 107, 03 Jan 1798, as viewed at https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.35112104867314?urlappend=%3Bseq=113 [7] Fairfax County Court Minute Book, 1797-1798, 16 April 1798, p. 216. [8] John Triplett, Map of a Road from Georgetown to Stevensburg. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib010949/>. [9] Fairfax County Court Minute Book, 1797-1798, 22 May 1798, p. 239. [10] Fairfax County Court Order Book, 1799-1800, 21 April, 1800, p. 489. [11] Fairfax County Court Order Book, 1799-1800, 21 April, 1800, p. 494. [12] Richard Ratcliffe, “To be Rented and Possession given about the 10th of next March,” Columbian Mirror, 27 Feb 1800. P.1, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [13] Richard Ratcliffe, “The Tavern of Fairfax County Court House to Let,” Columbian Mirror, 01 Nov 1800, p. 1, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [14] Fairfax County Court Minute Book, 1800-1801, 15 Dec 1800, p. 201. [15] “New Court-House Tavern: Messrs. Charles Hughes and Edward H Tucker,” Alexandria Times, 2 Jun 1801, p. 4, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [16] “For the Alexandria Daily Advertiser,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, 27 Oct 1803, Vol. 3, Issue 895, p. 2, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [17] Inhabitants Legislative Petition, 19 Dec 1804, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [18] Richard Ratcliffe Legislative Petition, 12 Dec 1804, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [19] Richard Ratcliffe Legislative Petition, 12 Dec 1804, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [20] Richard Ratcliffe Legislative Petition, 12 Dec 1804, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [21] “An ACT establishing a town on the land of Richard Ratcliffe, at the courthouse of Fairfax County,” Samuel Shepperd, The Statutes at Large of Virginia: From October Session 1792, to December Session 1906 [i.e. 1807], Inclusive, in Three Volumes, (new Series,) Being a Continuation of Hening ..., Volume 3, Chap. 69, p. 23, as viewed on Google Books. [22] “Notice is hereby given,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, 26 Jul 1805, p.4, as viewed at www.genealogybnk.com. Ad started running 2 Jul 1805. [23] Richard Ratcliffe Petition, 16 Dec 1811, Fairfax County, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [24] Richard Ratcliffe Petition, 16 Dec 1811, Fairfax County, Legislative Petitions of the General Assembly, 1776-1865, Library of Virginia, Legislative Petitions Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va. [25] Maddox vs. Ratcliffe, Superior Court of Chancery, BIC CI-CR-SC-11, CC: SC-4-1812, ID: 183-01, end year 1815, courtesy Fredericksburg Circuit Court, Fredericksburg, VA. [26] Allison vs. Ratcliffe, Superior Court of Chancery,BIC CI-CR-SC-H, CC: SC=H-1816 ID:10-24, end year 1826, courtesy Fredericksburg Circuit Court, Fredericksburg, VA. |

| Home |

|