| Finding Clues at the Ratcliffe-Allison House Oldest Sections Built ca. 1807 and ca. 1824 |

|

by Debbie Robison February 3, 2019 |

| BACKGROUND HISTORY |

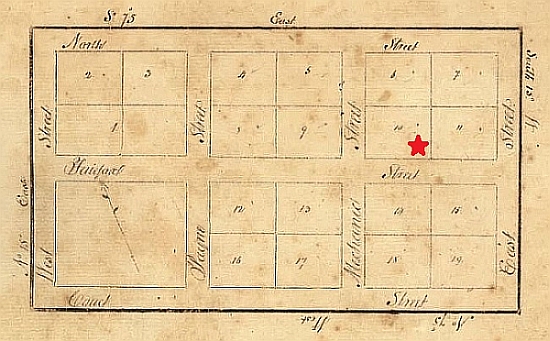

Ratcliffe-Allison House, City of Fairfax Henry Logan built, or had someone else build for him, a 1 1/2 story brick dwelling in the Town of Providence (present-day Fairfax City) fronting on the Little River Turnpike (now Main Street). The house has been known by many names, including Earp’s Ordinary (it was never Earp’s Ordinary), Ratcliffe-Allison house, Ratcliffe-Logan-Allison house, and the Ratcliffe-Allison-Pozer house. The house may have been constructed in 1807, the first year Henry Logan appears on the Fairfax County personal property tax ledger as living in his own household. Logan entered into a rent-to-own agreement with Richard Ratcliffe, the proprietor of all of the land in the town, for the eastern half of lot number 10 as depicted on the town plat.

Plat of the Town of Providence, 1811, by Robert Ratcliffe, Star

Depicts Location of Ratcliffe-Allison house. Ratcliffe agreed that if Logan paid ten years of rent within four years, Logan would get a deed for the half lot. This helpful information was found in a court case involving Richard Ratcliffe as the defendant. In a deposition, Ratcliffe asked a witness to confirm the Logan agreement.

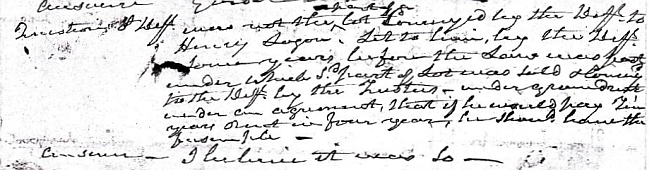

Deposition of Benjamin R Davis, Superior Court of Chancery, Courtesy Fredericksburg Circuit Court Question by Defendant [Ratcliffe]: Was not the part of a lot conveyed by the defendant to Henry Logan let to him by the defendant, some years before the law was passed under which said part of lot was sold and conveyed to the defendant by the Trustees, under ground rent, under an agreement, that if he would pay ten years rent in four years, he should have the fee simple? Answer: I believe it was so. The case includes other depositions that suggest that Ratcliffe did not build the house on the lot in anticipation of renting it to a tenant, as is commonly thought. He sold a lot without a house for $100 to Henry Logan. [1] Ratcliffe didn’t have clear title to the land due to the town trustees not issuing him a deed for the lots that he purchased at auction in 1805, so he petitioned the Virginia General Assembly in 1811 to have trustees issue him a deed. The deed to Ratcliffe for the town lots was recorded in 1812, immediately followed by a deed from Ratcliffe to Logan. [2] Henry Logan and his wife Sarah lived in the house and started a family. Their first child was born in 1807.[3] Four more children were born here before Henry Logan moved his family, including his mother and younger brother, to Parkersburg (now West Virginia) where Logan entered into the tanning and shoemaking trades. His mother, Mary Logan, was Mary Harmon before her marriage.[4] She may have been the sister of Peter Harmon who operated the tanyard nearby on lot 19. When Peter Harmon died in 1813, one of his debts was to Mary Logan.[5] Additional research is needed to prove the relationship between Mary and Peter Harmon.

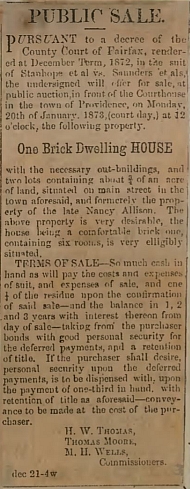

Sale Advertisement Logan sold the lot ca. 1813 to Hugh Smith, who was an agent for Gordon Allison & Co, a partnership of Gordon and Robert Allison. It may be that the Irish Allison brothers weren’t citizens yet, so the deed for the lot was issued to Smith as their agent. James Allison, their brother, had Hugh Smith enter into a deed for the store lot (part of lot 8) for that reason.[6] Gordon and Robert Allison, in conjunction with James Allison, operated a store, and later a tavern, on lot 8. A deposition taken in 1818 reveals that both Gordon and Robert Allison resided at the store/dwelling house on the other lot.[7] So, if Gordon and Robert Allison were living at the store, who was living at the Ratcliffe-Allison house at this time? Probably tenants. In 1824, the assessed value of buildings on the lot increased from $200 to $700, suggesting that the Allison brothers made substantial improvements to the house. This is likely when the addition was constructed.[8] By the mid-1830s, Gordon Allison & Co suffered financial losses and the company was forced to sell the property to Henry Taylor.[9] Gordon Allison’s wife, Elizabeth, died in 1837.[10] When Gordon Allison married Nancy Stanhope, Henry Taylor sold the Ratcliffe-Allison house property to a trustee for the benefit of Gordon Allison’s wife, Nancy.[11] That way, Gordon Allison’s creditors couldn’t ask a judge to sell the property to pay his debts. Taylor’s deed described the Ratcliffe-Allison house as two small brick tenements. The description of the house as two tenements suggests that the house may have been rented to tenants and that the interior doors between the two sections may not have originally existed. It is unknown when Gordon and Nancy Allison moved to the Ratcliffe-Allison house. After Gordon Allison died in 1854, his widow rented what she called another department of the house where she was living to Sybil Hunter.[12] Nancy Allison owned the dwelling until her death in 1872.[13] Following her death, her property was described in a sale ad as having one brick dwelling house containing six rooms, along with the necessary out-buildings.[14] This description may suggest that Nancy Allison no longer rented the house to tenants and that interior doors were installed to provide access between the two sections of the house. |

| CLUES TO PHASES OF CONSTRUCTION |

|

In 1995 and 1996, photographs were taken of the house for the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) by Jack E. Boucher. A review of the HABS photos and the existing building itself reveal a number of clues about the construction. |

| CLUE #1: FRONT JOINT |

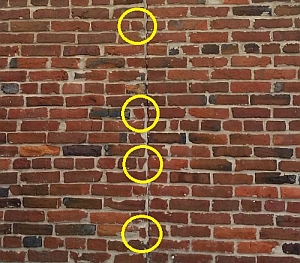

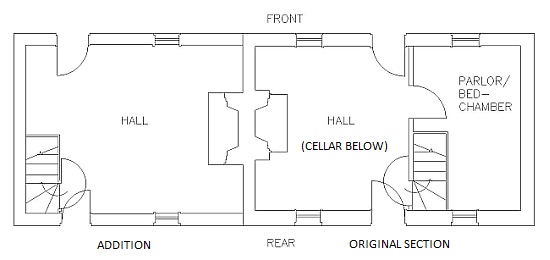

Joint Between Building Sections at House Front A joint between two sections of the house suggests that the 19th century portion of the house was constructed in two phases, and that the height of the original house was lower than it is now since the joint doesn't extend to the roof line. Contrary to common belief, the original section of the house is the larger western side. Note: When the National Register Nomination was prepared for the house in 1973, the author assumed the eastern side was the earliest section since, at the time, it was the only side that had a stairway. Another theory suggested that since the eastern side was approximately equivalent to the 16’x16’ minimum house size required by the act that created the town, then it was the earliest section. The original western side was constructed ca. 1807. When the eastern side was added ca. 1824, the roof line was raised. |

| CLUE #2: REAR JOINT |

Joint Between Building Sections at House Rear, When the eastern addition was constructed, the builder probably began building his exterior masonry walls at the front of the house abutting the original building, then extended the wall to the eastern property line. He continued around until he finished the exterior masonry walls at the rear joint. This sequence is suggested by the use of whole bricks at the front of the house at the joint, but only partial bricks at the rear joint. Once the builder reached the rear joint, he needed to fill the remaining distance with smaller pieces of brick. This is another clue that the eastern portion of the house was built second. Had it been built first, the bricks at the rear joint would have been whole bricks so they could turn the corner rather than abut an existing building. |

| CLUE #3: ORIGINAL STAIRWAY OPENING |

|

It appears that the original portion of the first floor was divided into two rooms separated by a stairway to the garret level. This type of configuration is referred to as a hall-parlor plan, which was common during this time period. The first-floor room with the fireplace may have been the hall, likely used as a dining room, and the adjacent room either a parlor or bedchamber. Once the children were born, the likelihood of using the downstairs room as a bedchamber increases, since the house was quickly filling up with occupants. The garret level was also likely divided into two rooms. Since the height of the house was initially lower, the windows on the garret level did not originally exist. In order to have natural light in the garret rooms, there may have been dormer windows. The following floor plan is a conceptual diagram of how the first floor may have looked once the addition was built.

Conceptual First-Floor Plan ca. 1824

Opening Between Joists at Original Stairway, The conceptual plan is based on clues found in the HABS photos, which show evidence of a former stairway that was later removed. The hand-hewn joists were spaced far enough apart to allow for access to the upper level. Typically, second-floor joists were placed about two feet apart on center. This anomaly in the regular spacing of joists was intentional. When the stairway was removed, a later joist that was sawn rather than hand hewn was installed in the opening to support floor boards on the garret level that infilled the opening. The original stairs were located just to the left of the front door, with the entrance to the staircase at the rear of the house. This configuration would have allowed enough headroom to climb the stairs. The stairs may have been constructed in a manner similar to the existing staircase located in the 1824 addition. The photo also shows that there was a light (probably white) coating on the joists and underside of the garret floor boards suggesting that the house didn’t originally have a plaster ceiling. The original owner may have foregone a plaster ceiling in order to save money. Note that the floor boards used to infill the stairway opening do not have the coating. A 1988 archaeology report by Malcolm L Richardson describes a cellar under the house. The cellar is under the hall of the original section of the house, ending where the stairway wall is shown in the conceptual plan. The stairway wall was likely bearing on the brick cellar wall directly below. Beneath the hall fireplace, the cellar wall has a chimney relieving arch, which is a niche that reduced the number of bricks needed. Entrance to the cellar was from the outside, likely through a cellar access hatch under the front center window. The cellar door opening, now infilled with brick, measured 3’ x 5’. [15] |

| CLUE #4: CHIMNEY BREASTS |

|

A big clue for determining which section of the house was built first was found by comparing the heights of the chimney breasts in each section of the house. The following photo shows the chimney breast in the original (western) portion of the house. When you are in the room, you can see the top of the chimney breast, and beyond that, the chimney containing the flues. You normally don’t get to see how chimneys were constructed because the chimney breast typically extends to the ceiling. This was likely the case here, and the ceiling height in this space was probably only about 6’-5” high when the house was first constructed.

Western Garret Room Showing Height of Chimney Breast,

Approximate Original Ceiling Line of Western Garret Bedchamber, When the eastern addition was constructed, the building height was raised. The chimney breast in the new garret bedchamber was constructed to a higher elevation so that it would extend to the new ceiling height.

Eastern Garret Room with Chimney Breast Extended to Ceiling, |

| CLUE #5: HAND-HEWN JOISTS |

Hand-hewn Joists, Photographer Jack E. Boucher, HABS, In addition to reviewing historical documents, the approximate age of the house can be confirmed by understanding how the joists were cut to size. The joists in this house were hand hewn, likely using an adze. Both the ca. 1807 and ca. 1824 sections of the house have hand-hewn joists. This was a period of technology change; some houses constructed at this time were made with joists that were cut at a water-powered sawmill. A few water-powered sawmills began appearing in the northern portion of Virginia around 1785, and in Fairfax County by 1793. Sawmills started to become popular manufacturing ventures at the turn of the 19th century. |

| CLUE #6: SECOND FLOOR ELEVATION DIFFERENCE |

Small Step at Doorway to Original Section of House, The two sections of the house may not have originally had doorways to provide access to the other side of the house. The first clue is from an 1842 deed that described the property as having two tenements, suggesting that different families lived in each section. The second clue is that the garret level on the western side of the house is higher than the garret level on the eastern side. A small step was needed to compensate for the different levels. If the intention at the time the addition was constructed was to have doorways between the sections, it’s likely the carpenter would have set the floor levels equal. |

| CLUE #7: MINERAL DOORKNOB |

Mineral Doorknob on First Floor Interior Door, Doors may have been cut through the brick walls on the first and garret levels when Nancy Allison owned the house. When she died and the house was advertised for sale in 1873, the house was no longer described as two tenements, but as a dwelling with six rooms. In this photo, it appears that the first-floor door between the two sections of the building had an upright rim lock with a glazed, variegated mineral doorknob. The variegated pattern was obtained by stirring different colors of clay together prior to firing. Production of mineral doorknobs increased in the late 1860s following the invention of pressing and molding machines.[16] The mineral knob was patented by John Pepper in 1851. He formed the Mineral Knob Company with the assistance of Cornelius Erwin, president of Russell & Erwin.[17] |

| CLUE #8: PLASTER HIDDEN BEHIND WAINSCOTING |

Plaster Behind Wainscoting, The wainscoting on the first-floor walls is not original. It was likely added after the house became a single dwelling rather than two tenements since the same wainscoting is present in both first-floor rooms. Plaster is behind the wainscoting, which can be seen where a portion of the wainscoting was removed. The original builder would not have plastered the wall if his intention was to install wainscoting. The ca. 1824 addition may have originally had a chair rail before the wainscoting was installed, a portion of which remained. This style of chair rail, with a bead on the lower edge, is appropriate for a ca. 1824 construction.

Chair Rail in Addition, |

| CLUE #9: NAILS AND SCREWS |

|

Screw with Off-Center Slot, The ca. 1824 stairway in the addition appears to be original. At least one early screw is present in this photo of the stairway door hinge. Note that the screw slot is not centered. Technology to manufacture screws with centered slots was being developed around this time, but not widespread. The photo also shows how the stairway door was constructed. It appears that machine cut nails were used to nail the boards to the ledges (horizontal support boards), and that the nails were cinched (bent over) on the back. A closer examination is warranted. The method of nail construction that would allow nails to be cinched came into use by the second decade of the 19th century, though perhaps not in this area until later. An 1816 house near Vienna was constructed with earlier nails that could not be cinched. |

| CLUE #10: SAW MARKS |

Underside of Second-Floor Flooring in Addition The floor boards in the addition are not original, since they appear to be tongue and groove floor boards. Technology to mass-produce tongue and groove flooring was invented in 1828 by William Woodworth who obtained a patent, but didn’t come into common use in the area until the 1850s after the first patent expired. The flooring on the second floor of the addition can be observed from below. It was sawn with a large diameter circular saw, based on the saw kerf marks left in the wood. This technology came into use in the 1840s, but was more predominant in the 1850s and onward. |

| CLUE #11: FLUE CHIMNEY GHOSTING |

|

When the HABS photos were taken in the mid-1990s, there was a ghost mark of a former flue chimney on the exterior wall of the western garret bedchamber. Flue chimneys were used to exhaust smoke from stoves and furnaces. They came into use after the Civil War, therefore the flue chimney was not an original feature of the house. A flue chimney was re-built in this location.

Flue Chimney Ghost Mark, Western Garret Bedchamber, Photographer Jack

E. Boucher, HABS,

Ratcliffe-Allison House General View |

| ENDNOTES |

|

[1] Allison vs. Ratcliffe, Deposition of Benjamin R. Davis, Superior Court of Chancery, BIC CI-CR-SC-11, CC: SC-4-1812, ID 183-01, end year 1815, Fredericksburg Circuit Court, Fredericksburg, VA. [2] Fairfax County Deed Book M2(39)135, Deed from Providence Trustees to Richard Ratcliffe; Also, Fairfax County Deed Book M2(39)137, Deed from Richard Ratcliffe to Henry Logan. [3] Grave marker for Susan Logan, Parkersburg, Wood County, West Virginia; Federal Census of 1860. [4] Biography of Henry Logan, unattributed, Ancestry.com. [5] Fairfax County Will Book L1(661)120, Estate Account of Peter Harman, June 1816. [6] Allison vs. Ratcliffe, Complaint of James Allison, Superior Court of Chancery, BIC CI-CR-SC-11, CC: SC-4-1812, ID 183-01, end year 1815, Fredericksburg Circuit Court, Fredericksburg, VA. [7] Allison vs. Ratcliffe, Deposition of Matilda Farr, Superior Court of Chancery, BIC CI-CR-SC-11, CC: SC-4-1812, ID 183-01, end year 1815, Fredericksburg Circuit Court, Fredericksburg, VA; Also, Richard Ratcliffe answer states that Gordon and Robert Allison lived at the store, 14 Jan 1817, same court case. [8] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library. [9] Fairfax County Deed Book E3(57)55, 20 December 1837, Deed from G&R Allison to Taylor. [10] Alexandria Gazette, 05 Jun 1837, p. 3, obituary of Eliza Allison. [11] Fairfax County Deed Book G2(59)207, 07 Jan 1842, Taylor to Richardson in Trust for Nancy Allison. [12] Nancy Allison vs. Sybil Hunter, Fairfax County Chancery 1859-041, image 20, Library of Virginia. [13] Alexandria Gazette, 20 Jan 1855, p. 3, obituary of Gordon Allison; Also, Virginia Death Index, 12 Jul 1872, Nancy Allison, as viewed on ancestry.com. [14] Lewis Stanhope ETC vs. Mary C Saunders, ETC, Fairfax County Chancery 1878-017, Image Courtesy Library of Virginia. [15] Richardson, Malcolm L, Earp’s Ordinary (The Ratcliffe-Allison House): A Rescue Project Site No. 44FX1065, Occasional Paper 88-1, The Northern Virginia Chapter Archeological Society of Virginia, September 1988, Virginia Room Rare Books Collection, Fairfax County Public Library. [16] Eastwood Maude, Mineral Doorknobs, as viewed at http://www.antiquedoorknobs.org/mineral%20knobs.htm. [17] Ball and Ball Co., A brief history of locks in America, as viewed at http://www.ballandball-us.com/lockhistory.html |

| Home |

|