| Frying Pan Baptist Meeting House | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| by Debbie Robison | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ESTABLISHMENT OF BAPTIST CHURCHES IN NORTHERN VIRGINIA | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

During 1760s, Baptists continued to emigrate from THE BAPTIST QUEST FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM |

| With the rise of the Baptists, men in power became

alarmed by their growth in numbers and stretched the interpretation of an

existing law for preservation of peace, seizing ministers and having them

arraigned for disturbing the peace. May it please your worships, these men

are great disturbers of the peace, they cannot meet a man upon the road but

they must ram a text of Scripture down his throat.[4]

Jeremiah Moore, who would later become the second minister at Frying Pan

Springs Church, was charged in 1773 with

preaching and publishing the holy Gospel without a license.[5] Patrick Henry was an advocate of religious freedom

who defended Baptist preachers in court [6]

and advised preachers to conduct marriage ceremonies as the most certain way of

gaining that right by law.[7]

Another statesman, James Madison, offered an amendment to the Bill of Rights

under consideration in the Virginia Convention of 1776, that no man ought on

account of religion to be invested with peculiar emoluments or privileges;

but this was not adopted. The Anglican Church clergy retained its sole right to

perform legal marriage ceremonies.[8] Virginia Deputy Governor John Blair compared Baptists

beliefs with those of the Anglican Church and wrote in a 1768 letter I am

told, they administer the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, near the manner we

do, and differ in nothing from our church but in that of Baptism, and their

renewing the ancient discipline, by which they have reformed some sinners, and

brought them to be truly penitent.[9]

The baptisms differed due to the Baptists insistence upon adult consent

baptism by immersion.[10] Several Baptist Associations petitioned the state for

religious freedoms that included, as an example, 1. That we be allowed to worship God in

our own way, without interruption. 2. That we be permitted to maintain our own

Ministers &c. and no other. 3. That we and our friends who desire it, may

be married, buried and the like, without paying the Parsons of any other

denomination. [11] INCEPTION OF THE FRYING PAN BAPTIST MEETINGHOUSE |

| With the desire to erect a meeting house convenient

to a spring on Robert Carter III’s Frying Pan Tract, members of the Oral tradition asserts that an earlier meeting house

belonging to the congregation burned during the American Revolution, though

some accounts stated that the meeting house was in a different location and

that portions of this destroyed structure were used in the construction of the

Frying Pan Meeting House. On May 13, 1791, a church covenant was agreed upon

and entered into the church minute book. The language in the covenant suggests

that the worshipers were already members of the DIVISION IN THE BAPTIST CHURCH |

| In the 1630’s, a Baptist group, called Particular

Baptists, emerged in variance with the established General Baptists. Particular

Baptists believed that Christ’s atonement was particular and only benefited

those who were predestined by God to salvation. General Baptists believed that

Christ’s atonement was general and benefited everyone. During the Great Awakening when revivals flourished,

a distinctive group emerged out of the Particular Baptists called Separate

Baptists. Their emphasis during worship was more emotional and included encouraging

sinners to repent. To distinguish themselves from the Separates, the balance of

American Particular Baptists became known as Regular Baptists.[17]

The Frying Pan Church members began as Regular Baptists. At its inception, Frying Pan was a member of the

Ketocton Association; but in 1820 broke off with nine other churches to form

the Columbia Baptist Association. The reason, documented many years later in

the minutes of the Shiloh Baptist Church in Fredericksburg, was that the

Association was unwieldly, had no constitution, some of the ministers were

contentious and the annual sessions were disturbed by vain janglings. The

association was considered unmanageable because its thirty-nine churches were

spread out in eleven counties.[18] A movement began in the first quarter of the 19th

century among some Baptists to engage in missionary work, promote religious

education through Sunday schools, advance temperance, and form societies for

the distribution of the Bible. A group of Baptist churches opposed to missions

held a belief in predestination that precluded attempts to lead others to

salvation. The opposition split from the Regular Baptists to form Old Baptist

congregations. In 1833, William Broaddus, a pastor in the Shiloh

Association who was a staunch believer in the missionary movement, was denied a

seat at the Columbia Association Meeting after Frying Pan’s pastor, Samuel

Trott moved to put the issue to a vote. Two years later, Frying Pan Church

members submitted a letter to their association asking if churches should

discontinue their involvement with Broaddus entirely. The association voted to

continue fellowship with him, resulting in five churches, including Frying Pan,

withdrawing from the organization. Four of these churches, along with others,

formed the Virginia Corresponding Meeting of Old School Baptists in 1836. [19] Another division occurred among the Baptists that

resulted in a split within the Frying Pan congregation. Baptists who called

themselves orderly Baptists held the belief that baptisms could only be

performed by administrators who had not been previously excluded from

fellowship by any of their churches due to disorder and unsoundness in

doctrine. For several years prior to 1889, when the split at Frying Pan

occurred, some Baptists acknowledged these baptisms. Orderly Baptists viewed

these members, whom they called Clark Baptist in the East and Means Baptist in

the West, as disorderly and their views as liberal. Division between the

Baptists occurred in the West in 1887-1888 and in DOCTRINE AND CONDUCT |

| The Frying Pan Church Covenant, in addition to

incorporating the principles contained in the Baptist Confession of Faith

adopted by the Association at 1.

That the Old and New Testaments are the infallible word of

God and guides to salvation. 2.

Salvation is through Jesus Christ as judged in the last day. 3.

There is only one God. 4.

Father, Son, and Holy Ghost make up one God. 5.

Jesus Christ, who died to atone for all sins, is the only

savior of sinners. 6.

The redeemed shall obtain eternal happiness. 7.

That Christ will resurrect the dead and receive the

righteous. The members also agreed to several rules of

discipline, paraphrased as follows: 1.

To attend worship and church business meetings unless good

cause for non-attendance is given at the next meeting. 2.

To pay funds, according to ability, to defray church

expenses. 3.

To not divulge infirmities of others, if legally possible. 4.

To not move residence without informing the church and

receiving advice. 5.

To walk in all the commandments and ordinances of the Lord. 6.

To bear reproof and to reprove each other in case of visible

faults. Any member who did not follow these principles was

liable to censure. Continuous disobedience resulted in exclusion from their

communion.[21] The Frying Pan Meeting House Minute Books contain

numerous entries describing accusations of violations of the rules of

discipline and replies by the accused. A sampling of early allegations and

indictments follows. ·

Thomas Harris excommunicated for Repeatedly getting Drunk

& ill behavior.[22] ·

Resolved that Sister Blinco be publickly excommunicated for

disorderly Behaviour and disobedience to the Church [23] ·

A Report spreading abroad to the prejudice of ·

Widow Thomas who was a Member with us, who unhappily are

found to be with Child without a Husband.[25] AFRICAN-AMERICAN BRETHREN |

| From its inception, African Americans, both free and

enslaved, were welcome to join the Frying Pan Baptist Meeting House

congregation.[26]

The church minute books periodically recorded the name of an enslaved

individual’s owner, though the owner was not always a member. This circumstance

suggests the possibility that a certain level of freedom of movement was

accorded enslaved individuals for the purpose of attending church. Alternately,

as was the case with Brother Thomas and his slave, Judah, owners and slaves

attended the same church.[27] Although African Americans were welcomed, they were

segregated from the rest of the congregation, both during life and after.

Within the meeting house, African Americans worshiped from the galleries that

lined both sides of the building. In 1833, the church appointed an African

American, Jupiter, to try to keep order among the coloured people in the

gallery in times of worship.[28]

Jupiter, who was not free, had long been called upon by the church to take a

leadership role with other African Americans.[29] When a complaint was laid against a Black

member Called Tom for Conduct disgraceful to the Christian profession,

Jupiter was nominated to give him notice.[30] Though the church did give Jupiter some

responsibilities, when a committee was formed to hear and settle grievances among

the African Americans, the grievances were not heard by a committee of peers.

Jupiter was not included on the committee, nor were any other African

Americans.[31] For several years, Jupiter was involved in a dispute

about whether he could preach. In June 1824, the minutes state that Brother

Jupittor a Coulered man is not Allowed to preach.[32]

The following year in July, the Case of Jupiter was called up in Relation to

his preaching the Church desided that he should not preach. But at prayer

meetings he might have the same privileges as other members in singing and

prayer.[33]

He was expelled from the fellowship of the church for Immoral Conduct in

1827[34]

and restored a year later.[35] In death, the enslaved and free African Americans

were buried in a segregated area of the graveyard located in the southeast

corner of the lot.[36] The African American brethren were held to the same

rules of conduct as all members and were censured or excluded. As an example,

in 1805 the church charged Victory, a Slave belonging to the widow Summers

with getting drunk. She was suspended from Communion.[37]

In another matter of censure, the church Agreed that Bill Talbert who passed

in this Neighbourhood for a free man, and has proved since his profession of

Religion to be a Slave Agreed that he be Excluded from our Society.[38]

Since the church did not exclude slaves as a matter of course, it may be

inferred that Talbert was not excluded for being a slave but for lying about

being free. The names of people baptized or accepted for

membership was recorded in the minute books; however, for the enslaved, their

name was sometime replaced by referencing their owners, e.g. Chas Turley’s

woman, Robert Thomas Woman, Mr Browns Man.[39] The church covenant requires members Not to remove

our residence or abode to any different part of the world without informing the

church and advising with our brethren. The church issued letters of

dismission to members in good standing to be used as an introduction to a

Baptist church at the place of their new residence. This requirement applied to

the enslaved as well, though the cause of their move may have been due to being

sold. Fanncy a Black Woman formerly the property of the Widow Buckly, but

sold to some person in Alexandria Dismist from us this 19th Apl 1817 to Join

that Church.[40]

One formerly enslaved individual, David, received a dismission from the Church

to emigrate westward upon the death of his owner.[41] Following the Civil War, in September 1868, a request

was made for members to attend church, especially the Coloured Members to

state the cause of their nonattendance since the war. Some were in

attendance and provided an answer that was satisfactory to the church.[42]

In December 1881, the church again requested an explanation for the cause of

declining attendance by African American members. The cause was explained that

these members were cold in the gallery without a stove but there was an effort

amongst themselves to buy one and have it put in the gallery.[43] WOMEN'S ROLES IN THE CHURCH |

| At

the Frying Pan Baptist Meeting House, women were not called upon to represent

the church or to speak their views during services. Only white men were

appointed as messengers to the Association meetings.[44]

During Elder E.V. White’s ministerial period, the male members were called

upon to give expression to any views or feelings they might have. [45]

Often, the Elder called upon the male members to let the church hear of

their Christian travel.[46] This

practice was consistent with biblical references in the New Testament, which

church members used as a guide to salvation. Let your women keep silent in

the churches, for they are not permitted to speak; but they are to be

submissive, as the law also says. And if they want to learn something, let them

ask their own husbands at home; for it is shameful for women to speak in church.[47] This

edict was not strictly adhered to when women wished to be accepted into the

church. Like any other, they were called to relate their religious experience

prior to acceptance and baptism.[48] Women

were not restricted from donating money to the church in support of the

Ministry. Minute book records as early as those from the 18th century record

subscriptions by women.[49]

In 1957, Sister Alston stated she would furnish paint for the exterior of

meeting house.[50]

Nine years prior, in a traditionally female role, she agreed to select the

material for the new linen for Communion Service.[51] BOUNDARY DISPUTES |

| When Robert “Conciliator” Carter wrote to offer two

acres of land to the trustees of Carter’s Copper Mine Tract, later known as the Frying

pan Tract was surveyed by William Harding on February 23, 1797 as a result of a

chancery action styled “Carter of Shirley &c vs Carter.”[54] Three days later, John Lewis, Junr. laid off two

acres of land at the place known by the name of Frying pan Spring for the

Meeting House tract.[55] In September 1822, Robert Ratcliffe surveyed the

tract depicting lot number 9 which was conveyed to Robert “Conciliator”

Carter’s unmarried daughter Sophia Carter.[56] Sophia Carter’s will, dated 16 April 1832, required

her executor to sell my tract of land lying in county of Fairfax reserving

to the Baptist Church the House and Ground whereon it stands, denominated and

known as Frying Pan Meeting House with free ingress and egress, so long as the

same be used as a House of Public Worship.[57]

On December 3, 1838, her executor, William H Fitzhugh, sold the land to Charles

Ratcliffe.[58]

Seven months earlier, the church agreead that the

Letter and Plat from Counciler Carrter giving the lot of ground to build

Fryingpan Meeting Huse in Ann Ratcliffe, who was devised the property

surrounding the church in her husband’s will, gifted the property to her

daughter Mary Bayard Ratcliffe on December 23, 1845.[61]

Mary Ratcliffe sold the property to Burr Gould on the third day of the following

February.[62] In another unsuccessful attempt at deed recordation,

the church members, on December 11, 1847, Mooved and Seconed that Brethren

Blincoe and Wm Cockrell be appointed a Committee to attend with Wm Guld to the

Survey and Estblsing the Corners of the Meeting House lot and also having the

same recorded in the Clerks Office of Fairfax County.[63]

Yet four years later, the minutes records an agreement for boundary arbitration

with Mr. Gould. It being stated to the church that Mr. Gould who holds the

property around our Meetinghouse lot, was willing for us to select three men to

whom he and we would refer for their decision the difficulty between us in

reference to the boundary and extent of our lot, the church agreed to proposed

to Mr Gould Mr. Mear Turley, Col John Reid and Mr. Jas Fox to whom we were

willing to refer the matter and abide by their decision.[64] On Christmas Day of 1858, Burr Gould sold 203 acres

of land adjoining the meetinghouse lot to his son, Roderic Gould.[65]

Over the succeeding years, the parcel was sold to various owners with the meets

and bounds of the legal description identifying a corner as the center of the

Frying Pan Spring.[66]

John F. Oliver purchased half of the tract in 1898. For over 62 years, the older church brethren passed

knowledge of the boundary lines and markers to the younger generations. This

knowledge was called upon in 1909 during a chancery case by the Trustees of

Frying Pan Baptist Church as complainants against W. M. McNair and Lucy D.

McNair. The dispute revolved around ownership of the spring; the church

claiming complete ownership. The case was left unsettled once the church

recovered Robert Carter’s letter and the 1797 survey from a previous church

clerk showing that the spring was located on church property. During the case,

Joseph Berry, the county surveyor, prepared the following plat.[67] In 1911, Joseph Berry prepared an additional plat

that depicted the meets and bounds of the church lot based upon the description

taken from the 1797 John Lewis survey starting at, alternately, the oak stump

and the large stone. These were overlaid upon DEVELOPMENT OF THE SURROUNDING COMMUNITY |

| The land in the area where the Frying Pan Baptist

Meeting House would be erected began to be settled in the first quarter of the

18th century. The course of Tenants leased acreages from land grant holders who

typically required the construction of an 18’x20’ house as a term of the lease.

Robert Carter’s 1783 letter indicates that at least two tenants on his rent

roll lived in the vicinity.[71]

John Davis, a diarist of travels, wrote in 1801 that Frying Pan was composed

of four log-huts and a Meeting house.[72] As the population in western CIVIL WAR AT FRYING PAN |

| The Frying Pan Church is situated adjacent to a road

that was used for troop movement in the Civil War. On June 16, 1861, Col. Maxcy

Gregg of the First South Carolina Infantry, traveled along the road with about

five hundred seventy-five troops and met Captain Terry’s troop of horse at the Evidently, Captain Terry’s cavalry was stationed at Frying Pan. In a report

dated August 1, 1861 by Philip St. Geo. Cocke, colonel commanding the Fifth Brigade,

Army of the Potomac, he reports that Major Wheat’s On July 12, 1861, just days before the Battle of First

Manassas, the first major land battle of the armies in Virginia, J.W. Reid, a

soldier of the Fourth Regiment of the South Carolina Volunteers in the Army of

the Confederate States of On December 20, 1861, J.E.B. Stuart,

Brigadier-General, commanding four regiments of infantry (1,600 men), 150

cavalry, and a battery of four pieces of artillery, advanced on union troops at

Dranesville, VA, several miles north of the church in an effort to protect most

of the Confederate’s wagons. An engagement ensued and Stuart, recognizing he

was out-manned and out-gunned, retreated with all the wounded that could be

located to a railroad cut. Following a short halt, they proceeded to The neighborhood surrounding the church was a popular

retreat for John Singleton Mosby’s partisan rangers. As a successful cavalry

scout for J.E.B. Stuart, Mosby was rewarded with his own command. In December

1862, Mosby met Stuart at Mrs. Ann Ratcliffe’s home just north of Frying Pan

Church. Her daughter, Laura, was a source of intelligence information. Mosby

proposed to Stuart that he be left behind to disrupt shipments of material to

the Union Army when the 1st Virginia Cavalry went into winter camp. About this time, the Federals, under Maj. Gen. Samuel

P. Heintzelman, U.S. Army, commanding Defenses of Washington, had established a

cavalry picket line in an arc through western Fountain Beattie, one of Mosby’s initial nine

rangers, participated in Mosby’s first

raid, an attack on January 5, 1863 on picket posts near Frying Pan Church. [79] A

week later, the raiders attacked a ten-man picket post at Frying Pan Church.

Two federal sentries were posted outside a small weather-boarded house while

the pickets slept inside. (Note: The text is not clear if the small house

refers to the meeting house.) The sentries were quietly captured before the

house was fired upon.[80]

The following month, Mosby was intercepted by Laura Ratcliffe as he headed

towards From August 1-8, 1863, Col. William D. Mann, Seventh

Michigan Cavalry, explored the area between Bull Run and the After arriving at several of White’s recently

deserted camps, Mann set out for Dranesville and Frying Pan on intelligence

that Stringfellow was headed that way. On Friday, August 7th, Mann engaged the

enemy who broke in all directions through the thickets. He captured 20

prisoners, mostly Mosby’s and White’s men. On September 1, 1863, Colonel Horace Sargent

complained about the hit and run tactics used by White and Mosby. ‘A policy of

extermination alone can achieve the end expected....Regiments of the line can

do nothing with this furtive population, soldiers to-day, farmers to-morrow,

acquainted with every wood-path, and finding a friend in every house....The rebels

never patrol roads in column, and we are not safe in bands of 3 or 4; every one

betrays us....I can clear this country with fire and sword, and no mortal can

do it in any other way. The attempt to discriminate nicely between the just and

the unjust is fatal to our safety; every house is a vedette post, and every

hill a picket and signal station.’[83] Following the war, E.V. White became a minister at

Frying Pan Baptist Meeting House in addition to owning White’s Ferry in Another cavalry skirmish at The Frying Pan Baptist Meeting House suffered damage

as a result of the encampments and skirmishes. From May 7, 1853 to August 10,

1867 there is a gap in existing minute book records. The first minute book

entry after the war noted that MEETING HOUSE |

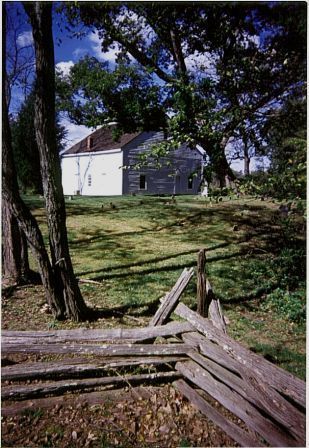

| The meeting house may have been built as early as

1783 when Robert Carter agreed to convey land to the church trustees of the Physical inspection of the meeting house revealed

that the structure was expanded by moving the southeastern and southwestern

corners. Based on the construction techniques and minute book documentation, it

is supposed that this major renovation work was performed by Mr. Weathers Smith

in 1796. The church minute book record of February 16, 1797 requests that all

the papers relating to the building of our Meeting house be brought

before the church So the Balance due Mr. Weathers Smith for work done on the

Same may be ascertained.[88]

Later that year, Brother Coleman Brown paid 5 pounds 1 ˝ shillings as his part

of the money due Mr. Weathers Smith.[89] Two

cast-iron stoves are currently situated in the meetinghouse and identified as

follows: One-burner

stove on west side of sanctuary: Isaac A Sheppard & Co

Patented 1865 Two-burner

stove on east side of sanctuary: No. 39 1880 Isaac

A. Sheppard created the firm of Isaac A. Sheppard & Co. in 1860 with four

other partners: Jonathan S. Biddle, James C. Horn, William B. Walton, and John

Sheeler. The company established the Excelsior Stove Works of Philadelphia in

1860 and, supposedly six years later, the Excelsior Stove Works of Baltimore. A

catalog for the company indicates that the Isaac A. Sheppard & Co Excelsior

Stove Works and Hollow-Ware Foundry in A

circa 1929 catalog, Number 53, for The Isaac A Sheppard Co of Maryland

Excelsior Stoves and Ranges, offered a WoodlanD wood stove having the date of

1880 on the side.[91] ENDNOTES |

| [1] Foote, p. 314. [2] Robert Baylor

Semple, History of the Baptists In Virginia, Church History Research and

Archives, [3] Ibid., p.

386. Also see church minute books, FCPA Collections, original books on loan

from the Primitive Baptist Library, [4] Foote, p. 315. [5] [6] Foote, p. 317. [7] Semple, as cited by Garnett Ryland, The Baptists of Virginia 1699-1926, The Virginia Baptist Board of Missions and Education, Richmond, Virginia, 1955, p. 105. [8] Hunt, Writings of James Madison, I, p. 41, as quoted in Ryland, p. 104. [9] William

Henry Foote, Sketches of Virginia: Historical and Biographical, New

edition with Index published 1966, John Knox Press, [10] Russell

R. Standish and Colin D. Standish, Liberty in the Balance, http://www.present-truth.org/Liberty/standish/liberty/litb25.htm#Top,

Chapter 25: “Struggle for Religious Liberty by the Baptists in [11] Ryland, p. 98. [12] Charles

James, Documentary History of the Struggle for Religious Liberty in

Virginia, Da Capo Press, [13]

Petition by part of the Bull Run and Little River Baptist Churches and others

to Robert Carter requesting grant of two acres of land to erect a meeting house

convenient to the spring., Virginia Baptist Historical Society, [14] Ken

Ringle, “The Day Slavery Bowed to Conscience”, The Also, Robert Baylor Semple, History Of The Baptists In Virginia (1810), Revised and extended by G. W. Beale (1894), Church History Research And Archives, Lafayette, Tennessee, 1976, p. 178. [15] Robert

Carter (of Nomini Hall) letter to members of [16] Minutes. [17] G.

Thomas Halbrooks, Congregational Worship, The Historical Commission of

the Southern Baptist Convention, [18] Shiloh Minutes, 1870, p. 18, cited by Garnett Ryland, The Baptists of Virginia 1699-1926, The Virginia Baptist Board of Missions and Education, Richmond, VA, 1955, p.199. [19] Ryland, pp. 245-251. [20] Church

Book of the Frying Pan Church, Fairfax Co., Va 1891, Minutes, pp. A-C.

Note: This minute book was a record book for the “orderly Baptist” minority who

split from the established [21]

Minutes, [22]

Minutes, [23]

Minutes, [24]

Minutes, [25]

Minutes, [26] Minutes, July 1831. [27]

Minutes, [28] Minutes, May 1833. [29] Minutes, 17 May 1828. [30]

Minutes, [31] Minutes, January 1830. [32] Minutes, June 1824. [33] Minutes, July 1826. [34] Minutes, April 1827. [35] Minutes, 17 May 1828. [36] Deposition of H. J. O’Bannon, Fairfax County Circuit Court, chancery case cff #288, Trustees of Frying Pan Baptist Church complainants against W.M. McNair, defendants. [37]

Minutes, [38]

Minutes, [39] Minutes, 17 May 1811. [40]

Minutes, [41]

Minutes, [42] Minutes, September 1868. [43]

Minutes, [44]

Minutes, [45] Minutes, 8 Apl 1882. [46]

Minutes, [47] Spirit

Filled Life Bible, Thomas Nelson Publishers, [48]

Minutes, [49] Minutes, 1794. [50]

Minutes, [51]

Minutes, [52] Carter letter. [53] Library of Virginia Land Office Grants, Book B, p. 145. [54] Chancery action styled “Carter of Shirley &c vs Carter”, heard throughout the years in various courts, i.e. High Court of Chancery, Superior Court of Chancery, ending with the Spotsylvania District for the Superior Court of Chancery, recorded in 1819, Fredericksburg Circuit Court, Collection CR-SC-H, Record ID 63-1. [55] Survey of meeting house tract, Fairfax County Circuit Court, chancery case cff #288, Trustees of Frying Pan Baptist Church complainants against W.M. McNair, defendants. [56] [57] [58] FX DB

B3:417, [59] Minutes, 12 May 1838. [60]

Minutes, [61] FX DB

K3:179, [62] FX DB

K3:263, [63]

Minutes, [64]

Minutes, [65] FX DB

A4:296, [66] FX DB

G4:472, [67] FX Chancery cff:288. [68] Ibid. [69] FX

Court Orders (CO) A:123, [70] Minutes, 13 May 1791. [71] Carter letter. [72] John

Davis, Travels of Four Years and a Half in the United Sates of [73] FX Road

Surveys 1840-1860, Road Box 1, Road From Frying Pan Road at Gunnell’s School to

[74] United States War Dept., The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies: Official records of the Union and Confederate armies, Govt. Printing Office, Washington, D.C., (1880 - 1901) as cited in http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/moa/browse.monographs/waro.html. [75] [76] Jesse Walton Reid, History of the Fourth Regiment of the S.C. Volunteers: Army of the Confederate States of America, Shannon & co., Greenville, S.C. 1892, pp. 19-21. [77] [78] [79] Hugh C. Keen and Horace Mewborn, 43rd Battalion – Virginia Cavalry – Mosby’s Command, H.E. Howard, Lynchburg, Virginia, 1993, as cited by http://www.mosbysrangers.com/bio/. [80] Virgil Carrington Jones, Ranger Mosby, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 1944, pp. 70,71. [81] Hugh C. Keen and Horace Mewborn, 43rd Battalion – Virginia Cavalry – Mosby’s Command, H.E. Howard, Lynchburg, Virginia, 1993, p.26. [82] http://www.mosbysrangers.com/rosters/d.htm. [83] This

Week in the Civil War, [84] Charles

Jacobs and Jarian Waters Jacobs, “Colonel Elijah Veirs White: Part II”, The [85] [86]

Minutes, [87] Semple, p. 384. [88]

Minutes, [89]

Minutes, [90] Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Encyclopedia of Contemporary Biography of Pennsylvania, Vol II., Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Bethlehem, PA, 1868. [91] Isaac A Sheppard Co, The Isaac A Sheppard Co of Maryland Excelsior Stoves and Ranges, c.1929, content cited at http://www.msinfobooks.com/cgi-bin/msinfo/htmlos.cgi/01662.2.37918863490#tcisme. |

Though Baptists arrived in

Though Baptists arrived in