| Fort Schneider Purdy's Farm, Annandale, VA |

|

by Debbie Robison January 24, 2014 |

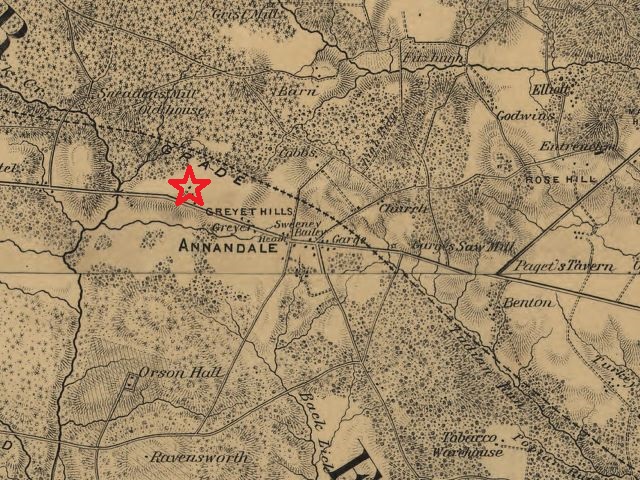

During the Civil War, Annandale Virginia was fortified to help protect

Washington, D.C. from Confederate guerrilla attack. A stockade-type fort was

constructed in the summer of 1864 adjacent to the Little River Turnpike on a

rise east of Accotink Creek. The fort was named Fort Schneider after Joseph

Schneider, Captain in the 16th New York Cavalry and commander of the

stockade.[1]

|

| DEFENSIVE STRATEGY |

The fort was proposed by Colonel H. M. Lazelle, 16th New

York Cavalry, Commanding Brigade, on July 19, 1864 after his force was reduced

when the Second Massachusetts Regiment Cavalry departed for Washington City.

Lazelle, who was responsible for overseeing observations of the enemy’s

movements up to the eastern side of the mountains, recommended a new defensive

strategy that was better adapted to his available strength (i.e. number of

troops). His scheme was to construct two defensible stockade forts, one at

Annandale and one near Lewinsville. The Annandale stockade would control the

Little River Turnpike and the Lewinsville stockade would guard two nearby

turnpikes. Three companies (one of which would be mounted) would be assigned to

each stockade. The remaining force, placed in a defensible camp near Falls

Church to control Falls Church village and the railroad, would constantly

patrol between the camp and the two forts.[2]

|

| PURDY’S FARM |

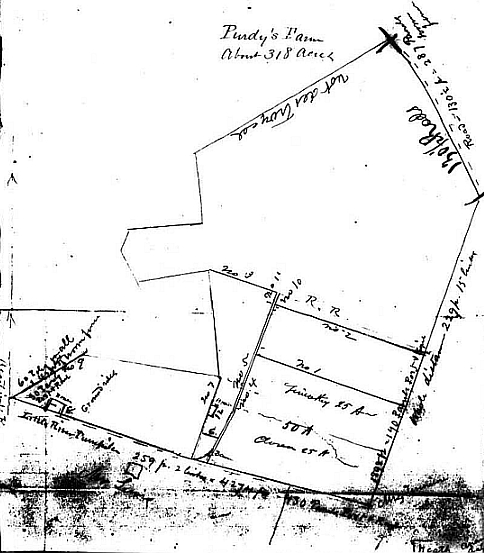

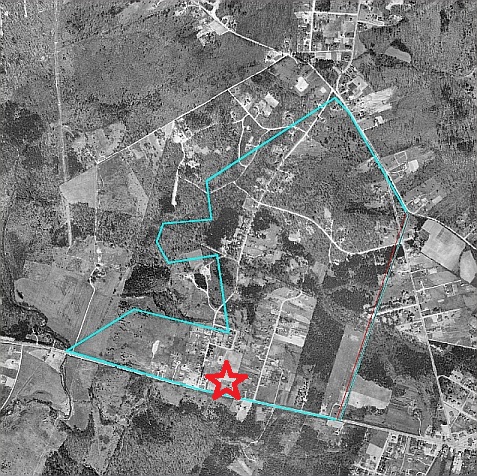

Fort Schneider was located on the land of James S. Purdy, a northern

man who was one of four who voted in his precinct against Virginia’s Ordinance

of Secession.[4]

Purdy’s family and property suffered during the war due to the strategic

location of his 318-acre farm. Purdy described his losses in a claim filed with

the Southern Claims Commission. Purdy stated that at the beginning of the war, he

furnished Union General Mansfield, the U.S. Provost Marshall at Alexandria, and

the Captain of nearby cavalry pickets with information on the movement of

Confederate soldiers. Knowing that Purdy was for the Union, the Confederates

searched his house and tried to capture him but he escaped to Washington. He

was threatened that if caught he would be killed rather than taken to Richmond.[5]

|

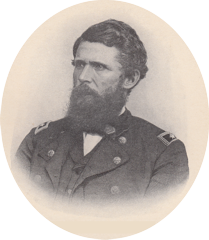

| Lafayette C. Baker |

About 3,000 trees, averaging 10” in diameter, were felled on Purdy’s

property by the 16th NY Cavalry for use in construction of the

stockade and abatis.[10]

An abatis was constructed at this site prior to construction of the stockade. Construction

of the fort began in July 1864.[11]

It likely encircled Purdy’s barn, which was used by the 16th NY Company

C as a stable for sick horses.[12]

On September 1, 1864, after an unsuccessful Confederate artillery attack,

Captain Schneider requested assistance with completing his stockade and abatis.[13] That

winter, additional timber was cut from Purdy’s farm for the construction of

winter cabins.[14]

The barn was pulled down for use in making sheds for horses and for use by a

detachment of the 5th Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery for building

winter quarters.[15]

The entire occupation embraced an area on Purdy’s farm of about 15 acres.[16]

|

| ATTACK ON FORT SCHNEIDER |

Early on the morning of Wednesday, August 24, 1864, the camp at the

Annandale stockade heard three warning shots fired by the picket on the Little

River Turnpike in advance of a Confederate attack. The fort, which was

positioned on a knoll, first came into view by the Confederates when they were

at the top of a hill about half a mile to the west. A valley was situated

between the Confederates and the fort.[17]

About 100 Confederates charged towards the entrance of the fort, but swerved to

the south and east when then were met be a volley. At the time, the stockade

held 170 northern troops of the cavalry battalion.[18] A flag of

truce was brought forward by the Confederates with a demand for surrender in

the name of Colonel Mosby. Under the flag of truce, they advanced two field

artillery pieces within 300 or 400 yards of the camp, one on the southwest and

one on the northwest. When the surrender was rejected, they began to fire shell

and grape shot into the fort. Two more requests for surrender, also issued

under flags of truce, were rejected. The last time a flag of truce was sent,

the bearer was informed that if they sent a flag of truce again they would be

fired upon.[19]

The attack lasted almost one and one half hours during which time the

Confederates fired from thirty to forty cannon shots. Union troops were

reported to have taken refuge in their bomb-proofs.[20] The

Confederate attack was unsuccessful, they claimed, due to the poor angle they

had for firing into the fort. They wounded two horses, but for the most part

their shots were ineffective. At the conclusion of the attack they retreated down

the turnpike toward Fairfax Courthouse.[21]

|

| IN THE END |

| James Purdy moved to New York an impoverished man. William H. Gooding, who owned the land that is now the Annandale Campus of the Northern Virginia Community College, sold the stockade and abattis for $150 in July 1865.[22] Purdy sold his farm in 1871.[23] He was successful in obtaining some of the funds he requested from the Southern Claims Commission as compensation for war-time losses, though he had difficulty proving portions of his claim due to his difficulty in obtaining accounts caused by the imperfect language skills of the German troops stationed on his property.[24] |

| ENDNOTES |

|

[1] Boston Evening Transcript, August 16, 1864, p4; New York Times, August 16, 1864. [2] United States War Department, “Report of Brig. Gen. John Newton, U. S. Army,” The war of the rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies, as viewed on http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu (Hereinafter referred to as Official Records), Chapter XLIX, July 19, 1864, pp. 387-390. [3] Official Records, Report of H. M. Lazelle, Colonel Sixteenth New York Cav., Comdg. Brig to Lieut. Col. J. H. Taylor, Chief of Staff and Assistant Adjutant-General, Chapter XLIX, July 19, 1864, pp. 387-390. [4] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy; Records of the Ordinance of Secession, Fairfax County Circuit Court Archives, Fairfax, VA; Federal Census of 1860 for James S. Purdy. [5] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [6] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [7] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [8] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [9] Lafayette C. Baker, History of the United States Secret Service, published by L. C. Baker, Philadelphia, 1867, pp. 197-200. [10] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com. [11] Official Records, Correspondence of H. M. Lazelle, Colonel Sixteenth New York Cav., Comdg. Brig., to Lieut. Col. J. H. Taylor, Chief of Staff and Assistant Adjutant-General, Chapter XLIX, July 28, 1864, pp. 481-2. [12] Official Records, Report of Capt. Joseph Schneider, Sixteenth New York Cavalry, Chapter LV, August 25, 1864, p. 638. Also Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com. [13] Official Records, Correspondence of J. Schneider, Capt. Sixteenth New York volunteer Cavalry, Comdg. Stockade to First Lieut. Edwin Y. Lansing, Actg. Asst. Adjt. Gen., Cavalry Brigade, Fort Buffalo, Va., Chapter LV, September 1, 1864, p. 4. [14] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [15] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [16] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [17] James Joseph Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers, Second Edition, Sturgis & Walton Company, New York, 1909, pp. 218-221. [18] Official Records, Report of G. A. De Russy, Brigadier-General of Volunteers, Chapter LV, August 24, 1864, p. 900. [19] Official Records, Report of H. H. Wells, Lieutenant-Colonel and Provost-Marshal-General, August, 24, 1864, pp. 637-638 [20] James Joseph Williamson, Mosby’s Rangers, Second Edition, Sturgis & Walton Company, New York, 1909, pp. 218-221. [21] Official Records, Report of Capt. Joseph Schneider, Sixteenth New York Cavalry, Chapter LV, August 25, 1864, pp. 638-639. [22] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com [23] Fairfax County Deed Book M4(91)270, James S. Purdy to Christian Seaman, March 22, 1871. [24] Southern Claims Commission, Claim of James Purdy, as viewed on ancestry.com |

| Home |

|

| © Debbie Robison, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved. |