| Conn's Ferry Fairfax County, Virginia Late-18th to Early-19th Century |

|

by Debbie Robison January 3, 2010 |

| PREFACE |

|

Transportation was important for the developing nation in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Goods were transported to port towns and markets, citizens traveled to court, families visited, and landowners traveled to their various landholdings. This is just a sampling of the reasons for travel along America’s early roads. Many of these roads led to ferries that were established at river crossings where the water was too deep to ford. A number of ferries could be found along the Potomac River, which separates Maryland from Virginia. Conn's Ferry Landing |

| HUGH CONN’S FERRY |

|

In the 1790s, Hugh Conn established a ferry across the Potomac River two miles above Great Falls. In 1790 he purchased 15 acres on the river from Joseph Porter and 50 acres, likely adjoining, from George Viall (Veal, Viley).[1] Conn later purchased Porter’s half interest in the land his wife and sister-in-law inherited from their father James Carter, who was the original land grant owner.[2] This collection of land, about 150 acres, made up what referred to as his tract of land at the ferry.[3] In October 1793, Hugh Conn, along with other Potomac River ferrymen, was required to keep travelers who may have yellow fever from entering Virginia. The governor of Virginia wrote to the Justices of Loudoun County requiring them to adopt some safe Mode for preventing the Introduction of the Pestilential disease (which now prevails in the city of Philadelphia the Granadies and the Island of Tobago) Into this State. At this time, Conn’s ferry was within the bounds of Loudoun County. The Justices called court and recommended that the magistrates establish regulations that there be stationed at each ferry a sergeant or corporal and four men whose duty would be to examine all persons who attempt to cross the river for satisfactory proof that they did not come from Philadelphia or its vicinity. If you were suspected of traveling from an infected area, you were not allowed to cross the river into Virginia for six days. During that time, your goods and baggage were exposed to the open air on the Maryland side of the river. If after six days you did not show signs of disease, the traveler was permitted to cross the river. If you suffered from some illness, a doctor was called to determine if the disease was yellow fever, and if it was, the traveler was compelled to return home. William Stanhope was appointed to make arrangements at Conn’s Ferry for providing the provisions of the guardsmen; including access to a horse should the doctor be needed. Stanhope could contract with anyone in the area who would provide the best terms, and the governor of Virginia agreed to pay for the provisions from the treasury. There were six other Potomac River ferries in Loudoun County that were also required to quarantine travelers: Edward’s, Myer’s, Noland’s, Heator’s, Smith’s, and Beltz’s ferries.[4]

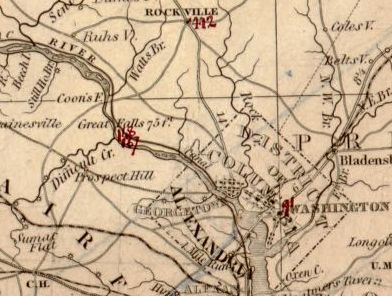

Conn’s Ferry Depicted on a Portion of Herman Boye’s A Map of the State of Virginia: reduced from the nine sheet map of the state in conformity with law, 1828 Corrected 1858. Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division Conn’s Ferry, located on the Potomac River north of Great Falls, is erroneously labeled Coon’s Ferry. |

| DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA BY A TRAVELLER |

|

When Irishman Isaac Weld, Jr. traveled through North America and Canada in the late-18th century he visited Great Falls, which he described in one of a series of letters that he published in 1807. Likely in the spring of 1796, Weld travelled from Montgomery Courthouse Rockville to the Maryland side of Great Falls. He then proceeded upriver until he reached a ferry where he could cross the river to view the falls from the Virginia side. The ferry he took was probably Conn’s ferry. Following is his description of the area: |

|

Isaac Weld, Jun., 1796[5] |

| INCOME FROM THE FERRY TRACT |

|

Conn kept both a boat and a canoe at the ferry landing to facilitate the business. He also used the land at the ferry to grow tobacco.[6] Many area farmers; however, had switched to grain cultivation at this time due to the high prices they were receiving for wheat and flour due to the European war. (See Late 18th Century Tobacco.) While there is no known record of Conn keeping a tavern at his ferry, he was charged in court for retailing spirituous liquors without a license.[7] Ferry rates were established by the Virginia General Assembly for each ferry. A typical rate in 1792 for a relatively easy crossing was 4 cents for each man and 4 cents for each horse. All other charges were based on the rate for horses. Coaches, chariots, and wagons, inclusive of their drivers, were charged at the same rate as six horses. Carts and four-wheeled chaises or chairs were charged at the same rate as four horses. Two-wheeled chaises or chairs were charged at the same rate as two horses. Each hogshead (large barrel) of tobacco and each head of cattle was charged the same as one horse. Smaller livestock, such as sheep, goats, lamb, and hogs, were assessed at one-fifth part of the ferriage for one horse.[8] When Hugh Conn died in 1806, he provided in his will for the

income from the ferry to support his widow, Susanna Conn, and their children.

However, if she remarried before the children reached 18 years of age, she

received the standard dower portion of 1/3rd of the land.[9]

She didn’t remarry during that period, and the ferry became known as In 1812, Susanna Conn, Rezin Elliott, Henry Conn, and Jesse

Conn, heirs of Hugh Conn, petitioned the Virginia General Assembly for a law to

legally establish a ferry across the Potomac River.

They acknowledged that Hugh Conn and they themselves, since Hugh Conn’s death,

kept a boat for the purpose of ferrying people over the |

| LOCATION OF CONN'S FERRY LANDING |

|

Evidence suggests that Conn’s ferry landing was located at the same place that is currently used as a boat ramp at the Fairfax County Park Authority’s Riverbend Park. Sketch Showing the Location of Conn's Ferry Based on Recent USGS Maps and Historical Surveys. The location of the ferry landing on the Conn property is known from two sources. A land dispute between Spencer Jackson and James Roberts, whose disagreement was over the land just south of the ferry, resulted in a survey being made of that property in November 1824. George Gunnell, who performed the surveyed, was taken to Mrs. Conn’s ferry, which was the starting point of his survey.[13] The second source is an excellent survey plat prepared in

1818 when a canal was contemplated from Goose Creek

in Loudoun County

to Hunting Creek near Alexandria.

By this time, Mrs. Conn was living in a house on the north side

of the road leading to the ferry. The house was located up on a hill and had a

porch and nearby kitchen.[14]

Both the ferry crossing and Mrs. Conn’s house are depicted on the

plat.[15]

(See Survey Plat at Library of |

| CONN’S FERRY ROLE IN THE WAR OF 1812 |

|

Conn’s Ferry achieved its moment of fame during the War of 1812 when President Madison crossed the Potomac at Conn’s Ferry on the morning of August 26, 1814 during his flight from Washington when the British burned many public buildings there. He and his party had reached the river the night before, but were unable to cross due to bad weather. Charles Ingersoll wrote in 1849 in his Historical Sketch of the Second War between the United States of America and Great Britain that Madison spent the night in a hovel in the woods before taking the ferry the next morning.[16] |

| CONN’S SLAVE, ELLICK, ESCAPES TO FREEDOM |

|

Hugh Conn was a slave owner, and likely had some of his slaves working his tobacco and corn fields. Other slaves probably raised Conn’s farm animals, primarily hogs and dungle fowl (chickens), though Conn also had some steers, geese, turkeys, and ducks.[17] The unpleasant sight of slaves toiling in nearby tobacco fields was noted by Isaac Weld Jr. when he traveled from Frederick Maryland to the Great Falls in 1796. Near Frederick he observed that the fields of the German immigrants were well cultivated and green with wheat. However, as he travelled through Montgomery County, Maryland and got closer to the Great Falls he saw a disappointing change in farm management. |

|

…large pieces of land,

which have been worn out with the culture of tobacco, are here seen lying

waste, with scarcely an herb to cover them. Instead of the furrows of the

plough, the marks of the hoe appear on the ground; the fields are overspread

with little hillocks for the reception of tobacco plants, and the eye is

assailed in every direction with the unpleasant sight of gangs of male and

female slaves toiling under the harsh commands of the overseer…[18] |

|

At his death in 1806, Hugh Conn owned eleven slaves. His estate inventory, appraised in 1809, valued the slaves from $3.34 to $333.34. The slave deemed most valuable was a man named Ellick.[19] He was about 27 years old at the time. When Conn’s estate was divided among his heirs, Ellick was given to one of his daughters, though she was not yet of legal age. Therefore, her mother, Susanna Conn, had responsibility over Ellick until her daughter was old enough to manage her own affairs. In actuality, Mrs. Conn’s son Jesse is known to have taken over this responsibility. Jesse Conn, representing his mother, hired Ellick out to James Hamilton, of Leesburg Virginia, for $80 for the year of 1817. After having worked for Hamilton for about two weeks, Ellick was arrested and convicted of breaking into the store of Mr. Joseph Beard. As punishment he was whipped and burned in the hand. The jailor released Ellick and told him to “clear yourself home you son of a bitch.” An observer to Ellick’s whipping and subsequent release asked the jailer if Jesse Conn was present, and the jailer replied that he didn’t believe he was. Ellick evidently took this opportunity to escape. About two months later, he was seen in Leesburg in the company of two or three men who captured him. They placed him in the Leesburg jail overnight, then retrieved him in the morning and continued on to Mrs. Conn’s house at the ferry. Once there, a couple of hours before sunset, the men entered the house to converse with Mrs. Conn, who had been lying down at the time. Ellick had been handcuffed and was left outside at the edge of the porch. Mrs. Conn refused to take charge of Ellick since her son was not at home. She sent a servant to Great Falls to ask Jesse Conn to return and handle the matter. At one half hour before sunset, a servant boy came into the house and told the men, who had been dining at the time, that Ellick had gone over the hill. The men jumped up and asked which way they should pursue him. Mrs. Conn told them he most likely had gone towards the river. At the ferry, the men met up with Jesse Conn and inquired if Mr. Conn had seen a black man. They explained that they brought home a slave belonging to the woman that lived in the house on the hill and that they were afraid that he had run away. The men returned to the house and remained there all night and the next morning insisted that they be paid for the expense of putting Ellick in jail and for travel expenses. Mrs. Conn refused to pay the men since Ellick escaped before Jesse Conn arrived to take charge of him. The men alleged that if they weren’t paid for these services that Ellick might even go back to where he had been taken and no person would apprehend him. Jesse Conn then allowed the men to take all of the money they found on Ellick (about $7) plus a few dollars more in additional compensation. The demand for compensation, and the threat that no one would expend effort in the future to return a slave to the Conns if the men weren’t paid, suggests that the men may have been slave hunters who were in the business of capturing and returning slaves for money. On the second morning after Ellick escaped, Jesse Conn traveled to Shepherdstown (now West Virginia) in search of Ellick guessing that Ellick would go up the Potomac River in a boat. Upon reaching the town, Conn did not hear anything about Ellick and therefore had handbills printed offering a reward for Ellick’s return. He also placed an advertisement in the August 30, 1817 National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser newspaper offering a reward for his return. |

|

$30 reward for runaway, negro Elleck, age about 35 yrs. – Jesse Conn, lvg in Fairfax County, Va. [20] |

|

Ellick, overcoming great odds, was successful in his bid for freedom. The Conn’s never saw Ellick again, though there were some rumors that he had been seen in Alexandria, Virginia. [21] |

| SUBSEQUENT OWNERSHIP AND USE |

|

Hugh Conn’s heirs sold the tract at the ferry to John Coad in November 1830.[22] He then sold a 50-acre portion of the tract with the ferry to Henry Dawes the following year.[23] It is unknown when the ferry discontinued operations. The land changed hands several times before being purchased in 1909 by Dr. John Ladd.[24] He built several cottages, buildings, and wells with well houses for the River Bend Camp he operated there.[25] |

| ENDNOTES |

|

[1] Loudoun County Deed Book (LN DB) S:310, 312, August 19, 1790, Conn’s purchase of 15 acres on the river from Joseph Porter. Also, LN DB T:179, 180, August 13, 1790, Conn’s purchase of 50 acres from George Viall, who had purchased the land from Joseph Porter in 1787 (LN DB S:160, June 9, 1787, Joseph Parker to George Viall.) [2] LN DB U:48, May 9, 1792. Also LN DB W:142, September 9, 1795. [3] Fairfax County Will Book (FX WB) I1(658):524, written July 2, 1795, probated July 21, 1806. [4] Loudoun County Order Book P, pages 272-273, including the unnumbered page between 272 and 273. [5] Isaac Weld, Jun., Travels Through the Stated of North America, and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, Fourth Edition, Vol. I, Printed for John Stockdale, London, 1807. Courtesy Library of Congress, American Memory. [6] FX WB J1(659):182, September 4, 1806, Appraisal on Inventory of Hugh Conn, deceased. The boat and canoe were valued at $25 and the crop of tobacco at $48. [7] Loudoun County Order Book (LN OB Q (Sept 1794 – Oct 1796), p. 103. [8] William Waller Hening, Henings Statutes at Large, Vol. 13, 1789-1792, William Brown Printer, Philadelphia, 1823, p. 565. [9] Fairfax County Will Book (FX WB) I1(658):524, written July 2, 1795, probated July 21, 1806. [10] Fairfax County Land Causes, page 103, November 11, 1824. Survey by George W. Gunnell of an adjacent property in the suit of Spencer Jackson vs. James Roberts, Gunnell notes that the plaintiff conducted him to Mrs. Con’s Ferry on the Potomack. [11] Fairfax County Will Book (FX WB) I1(658):524, written July 2, 1795, probated July 21, 1806. [12] Fairfax County Legislative Petitions, December 11, 1812, microfilm, Fairfax County Public Library, Virginia Room. [13] Fairfax County Land Causes, page 103, November 11, 1824. Survey by George W. Gunnell of an adjacent property in the suit of Spencer Jackson vs. James Roberts, Gunnell notes that the plaintiff conducted him to Mrs. Con’s Ferry on the Potomack. [14] [15] A plan and profile of an unfinished survey and level for a proposed canal from Goose Creek in Loudoun County to Hunting Creek near Alexandria, Library of Virginia, Board of Public Works Entries, #686, May 5, 1818. Viewed online at http://lvaimage.lib.va.us/BPW/indexes/685-694.html on December 31, 2009. [16] Anthony s. Pitch, The Burning of Washington; The British Invasion of 1814, Navel Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 1998. p. 128. [17] Fairfax County Will Book (FX WB) I1(658):524, written July 2, 1795, probated July 21, 1806. [18] Isaac Weld, Jun., Travels Through the Stated of North America, and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, during the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797, Fourth Edition, Vol. I, Printed for John Stockdale, London, 1807. Courtesy Library of Congress, American Memory. [19] Fairfax County Will Book (FX WB) I1(658):524, written July 2, 1795, probated July 21, 1806. [20] Joan M.

Dixon, National Intelligencer and [21] Loudoun County Chancery Case M7213 (1827-039) James H. Hamilton, et. al. vs. Susannah Conn, et. al, 1827. [22] FX DB Z2(52)324, 13 Nov 1830 [23] FX DB A3(53)153, 31 Oct 1831 [24] FX DB C7(159)573, 14 Jun 1909 [25] FX DB T9(228)597, 12 Jun 1926 |

| Home |

|