|

|

Chantilly,

VA was named after an early-19th-century

farm and mansion that was located on the north side of Lee-Jackson Memorial Highway (Route 50)

directly across from the Chantilly Regional Library. At that time, Lee-Jackson Memorial Highway

was known as Little River Turnpike.

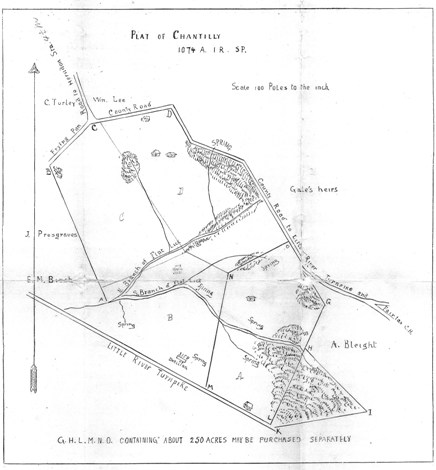

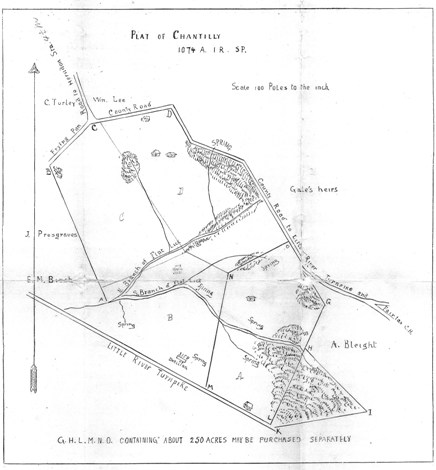

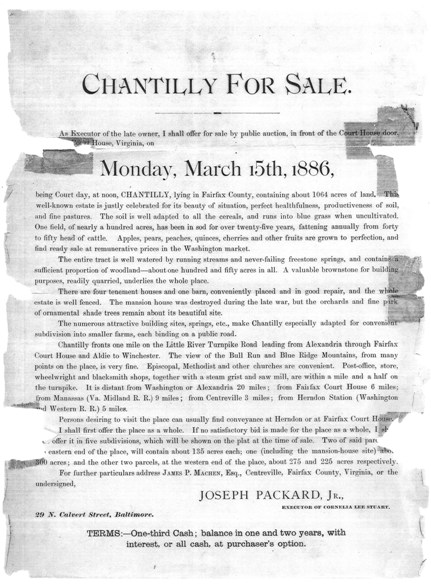

Plat of Chantilly, 1886

Charles Calvert Stuart had his Chantilly

mansion constructed on land his wife, Cornelia Lee Turberville

Stuart, inherited from her father’s estate in 1817.[1] The

mansion was probably constructed through the efforts of his slaves, many of

whom he inherited with the land.[2] By

the following year, the Stuarts were living at Chantilly.[3] In

1820, the buildings at Chantilly were

comparable in value ($2,000) to the buildings at nearby Sully. But by 1823, significant

improvements were made, perhaps through additions or new outbuildings. This is

suggested by the building values at Chantilly that

increased substantially to $3,438. Additional improvements made in late 1826 or

early 1827 brought the value to $3,750.67.[4]

Stuart became greatly indebted to his Sully neighbor,

Francis Lightfoot Lee, for the sum of $5,707.66; and entered into a trust

agreement in 1843 with Lee’s representatives, using the Chantilly

farm as collateral to secure the note. A debt was still outstanding when Stuart

died three years later, and it fell to his widow, Cornelia, to pay the funds.

She continued to live at Chantilly; though her

son, Sholto Turberville

Stuart, lived with her and acted as her agent in the management of her farm.[5] The

trust was released in 1853, suggesting that S. T. Stuart satisfied the loan

prior to the outbreak of the Civil War.

The mansion house has been noted for its regal splendor, and had beautiful shade trees, shrubbery, walks,

arbors, and fountains.[6] When

Charles Calvert Stuart died in 1846, his home was mentioned in his obituary: Chantilly, his family residence, will long be

remembered by warm hearted Southerners, as the seat of the most liberal and

elegant hospitalities.[7]

Like his father, S. T. Stuart used enslaved individuals as

house servants and farm workers. In 1855, four slaves ran away from Chantilly: Trolious Riley,

Henry Riley, Douglas Riley, and Vincent. Trolious

Riley was described as a house servant, and Henry Riley as a farm hand. Stuart placed

a $400 reward for their return, suggesting that their flight was assisted by some Abolitionist living in Fairfax County.[8] Nevertheless,

their escape was unsuccessful, as the four men were captured at the Point of

Rocks.[9]

| |

|

S. T. Stuart was an advocate for secession from the Union, though he was quick to point out that he

considered the step as a last resort only after Congressional negotiations

failed. On January 21, 1861, before a large crowd gathered at the Fairfax

County Courthouse to hear the speeches of the two candidates to the Virginia

Secession Convention in Richmond

(Alfred Moss and William H. Dulany), Sholto T. Stuart was called to make a speech. In the days

following, he wrote a letter to the editor explaining his speech:

| |

I said that it was

well known I had held to the most conservative grounds with the hope of

preserving the Union, that I was attached to that Union and knew and

appreciated its value to South as well as North, and I hoped it would be

reconstructed, if it could not be preserved; that I had looked anxiously to

Congress for an adjustment of the controversy…but all this coupled with the

failure to accomplish any thing by the noble Crittenden, had forced me to give

up all hope of a settlement in that way… I believed the safety and honor of Virginia demanded that

immediately, she should resume the powers delegated to general government. That

you might call it secession, revolution, or what not, I cared very little about

names where results were the same.[10]

|

|

Chantilly suffered due to

the Civil War, and was a site of occupation. It featured in the Battle of Ox

Hill as the starting point of Winder’s brigade’s march towards the battlefield.

Major H. J. Williams, of the Fifth Virginia Infantry commanding Winder’s

brigade, reported that on September 1, 1862,

Winder’s brigade, Col. A. J. Grigsby

commanding, was thrown into line of battle near Chantilly (the residence of Turberville Stewart, esq.) and

marched forward in supporting distance of Starke’s brigade to Ox Hill, a

densely-wooded crest overlooking the little village of Germantown…[11]

Primarily, Chantilly was

used during the war as a Federal cavalry headquarters, first by General Stahel, then by Col. Percy Wyndham.[12] By October 1862, the house was deserted and

dilapidated, personal family papers were scattered about, and all of the

furniture was reportedly removed except for an old-fashioned mahogany sideboard

that was too heavy to lift. Chantilly was a strategic point in the line of

defenses around Washington,

D.C., and at that time, the house

was occupied by Union troops on picket duty. A newspaper correspondent wrote: The outbuildings are in equally unoccupied

and dilapidated condition. The lawn, flower garden, fruit and shade trees are

all neglected, the fences are down, and cavalry horses roam at will over this

once truly magnificent spot. [13] Brigadier-General

Stahel reported that Col. Wyndham had 492 cavalry

troops stationed at Chantilly; and that of that

force, 140 men were on picket and patrol duty. Subsequent reports were filed by

Col. Wyndham from HEADQUARTERS CAVALRY

BRIGADE, Chantilly, Va.[14]

Though the cavalry at Chantilly

were under orders to be prepared for a long and rapid march, the men were able

to make some temporary provisions against winter weather. Following a snow

storm, a New York Times correspondent

traveled from Centreville and described the camp at Chantilly

in his report.

| |

...The troops at this

point have not gone into Winter quarters, nor do many

of them desire or expect to do so. As at Centreville, the infantry and cavalry

have made the best temporary arrangements possible for protection against the

weather. Fortunately, there are forests of pine trees at hand, and these have

been used freely in the construction of huts for the men and sheds for the horses.

Although no arrangements had previously been made for the horses, the whole of

the cavalry brigade commanded by Col. WYNDHAM, of the First

New-Jersey Regiment, was yesterday put under cover. The sheds, constructed of

poles and pine boughs make quite as comfortable quarters as the ordinary

stables in the colder latitudes. Other brigades are to-day imitating the

example set them by this command…[15]

|

|

Several incidents occurred while the cavalry was stationed

at Chantilly. In November 1862, the main force

of Calvary under Brigadier-General Stahel and Colonel

Wyndham advanced from Chantilly toward Ashby’s

Gap where they found 400 of White’s cavalry. Brigadier-General Stahel attacked them at Snicker’s Ferry and Berryville,

capturing nearly all their officers except White; and took their colors, 40 men

with horses, a wagon load of pistols and carbines, 80 cattle, and 80 horses.

Afterwards, the cavalry troops returned to camp at Chantilly.[16]

Capt. John S. Mosby, of the Virginia Cavalry, attacked the

picket post in front of Chantilly on March 23,

1863. Lieut. Co. Robert Johnstone’s vedettes gave the alarm, and 70 Union men were immediately

under arms and charging the Confederates for two miles along the Little River

Turnpike (now Route 50) to a point between Saunders’ toll-gate (which was

located at present-day Centreville

Road and Route 50) and Cub Run. Mosby had his men

feign a retreat to draw the Federals away from camp, then hid in the woods at a

point were the Union troops had blockaded the road. Once the Union cavalry was

within 100 yards of Mosby, he ordered a charge, and chased them for 4 or 5

miles. Five Federal soldiers were killed, a considerable number were wounded,

and 36 men were taken prisoner by Mosby’s cavalry.[17]

On October 17, 1864, over a year after the Mosby skirmish,

an Affair occurred at Stuart’s, near Chantilly.

No supporting reports were filed, thus the details of this action are

unknown.[18]

| |

|

Sometime about February 1863, Federal troops destroyed Chantilly by fire. The Philadelphia Inquirer printed a

letter written from the headquarters of the Eighteenth Pennsylvania Dragoons at

Chantilly stating that …The spot upon which we are encamped teams

with reminiscences of times both old and new. I mean the “Chantilly

Manor.” The “Hall,” which was once a splendid mansion, is now in ruins…It

had previously been suggested that Chantilly was burned because the Federal

troops mistook the house as belonging to Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart or

that White's guerrillas burned it; however, this letter provided another reason:

that Federal troops… became tired of

“standing guard” around a set of bacchanalians.[19] [drunken revelers]

Mrs. McGuire, a friend of Cornelia Stuart’s, wrote the

following in her diary:

| |

....Our dear friend Mrs. Stuart had

just heard of the burning of her house at beautiful Chantilly.

The Yankee officers had occupied it as head-quarters and, on leaving it, set

fire to every house on the land, except the overseer’s house and one of the

servants’ quarters. I expressed my surprise to Mrs. S. that she was enabled to

bear it so well. She calmly replied, “God has spared my sons through so many

battles, that I should be ungrateful indeed

to complain of anything else.”[20]

|

|

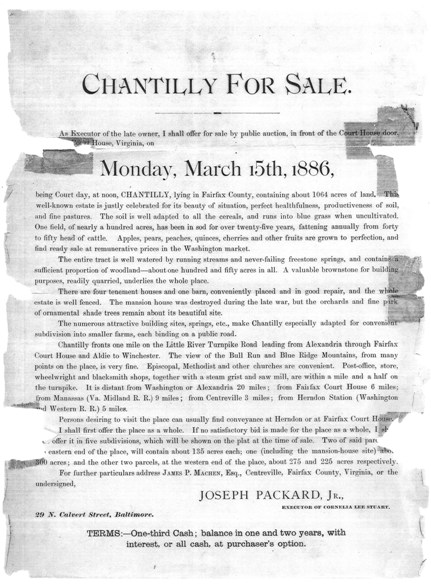

Following the war, at the close of 1865, Cornelia Stuart

needed to borrow $5,000, and used Chantilly

for collateral. Additional debts were secured by the property in 1879.[21] When

Cornelia died in 1883, she was deeply in debt, necessitating the sale of the Chantilly farm. A broadside advertised that there were four

tenement houses and one barn on the property.[22]

One of these tenement houses was the stone house that exists today.

| |

|

Perhaps in the 1820s, when the Stuarts were improving their

property, they had a stone house constructed along the Little River Turnpike

(now Route 50) using red sandstone quarried on the property. The stone house

exists today, and is located across from the Greenbrier Shopping Center.

The stone house may first have been a tavern; providing

food, lodging, and alcoholic beverages to travelers heading west to Winchester or east to the port of Alexandria.

When Charles Calvert Stuart died in 1846, he possessed many items that suggest

he may have been operating a tavern at the time; most notable were the 59

chairs, 14 beds, 28 pairs of sheets and pillowcases, 9 decanters, 84 glasses of

different types, 23 milk crocks, and 4 salt cellars (used to dispense salt at

the table).[23]

Chantilly Stone House, ca. 1823

Local tradition also asserts that the stone house was a tavern, and it is suggested

by its proximity to a turnpike; however, no definitive evidence has been

uncovered so far to support a firm conclusion that the stone house was a

tavern.

Local tradition also claims that the stone house was the

home of the farm’s overseer. During the Civil War, Mrs. McGuire, a friend of

Mrs. Stuart’s, wrote in her diary that Yankee

officers… set fire to every house on the land, except the overseer’s house and

one of the servants’ quarters.[24] This

diary entry lends credence to the supposition that the stone house was the overseer’s

dwelling.

In later years, the stone house was rented as a residence.

In 1883 and 1884, P. P. Thomas was a tenant in the stone house. It is also

possible that the stone house was rented to Lysander Wrenn.

Estate accounts note that the rent for the stone house was in arrears per a

letter from the sheriff. The sheriff, G. A. Gordon, wrote that Lysander Wrenn had no property on which to levy. Following the death

of Cornelia Lee Stuart, the Chantilly farm (with

four tenement houses, including the stone house), was advertised for sale to

pay Cornelia’s debts.[25]

George W. Powell was the purchaser of the stone house and 127 acres in 1888.[26]

It remained in the Powell family until 1943, when it was purchased by C. E.

Hutcheson and Edith Hutcheson, his wife.[27]

The Hutchesons were likely the

residents who renovated the stone house, including infilling one of the front

doors. A careful look at the house will reveal the original stone lintel that

exists above where a second doorway used to be located. In 1964, a portion of

the property between the house and the road was condemned by the Commonwealth of Virginia so that the road could be widened.[28]

The stone house was not always as close to the road as it is today. At present

the stone house is owned by the International

Town and Country Club.[29]

N.B.: Chantilly was likely

named after the home of Richard Henry Lee. He was a key 18th-century

politician, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Cornelia Lee Turberville Stuart’s grandfather. Chantilly

may occasionally have been pronounced with a southern accent; i.e. Chantilla. This is suggested by several 19th-century

maps that use this erroneous spelling.[30]

Charles Calvert Stuart was the half-brother of Eleanor Parke

Custis and George Washington Parke Custis, who were raised by George and Martha Washington.

Previously, the stone house has been erroneously called the Ayre House; however, the Ayre’s

owned different property nearby.

[1] Fairfax

County Deed Book (FX DB) S2(45):330, division of the

estate of George Turberville, May 1817. Charles

Stuart, Eleanor (Nelly) Parke Custis, and George

Washington Parke Custis share a mother, Eleanor

Calvert Custis Stuart, whose second husband was Dr.

David Stuart.

[2] FX DB S2(45):330, May 1817.

[3]

Financial and Legal Papers of Solomon Parsons refer to farm called “Chantilly”

in Fairfax County

on 01 Sept 1818, Papers of the Janney and Related

Gilmour and Pollock Families, Alderman Library, University of Virginia.

[4] Fairfax County Land

Tax Books: 1820, 1823, 1827.

[5] Mrs.

McGuire, “Diary of Mrs. McGuire,” in The Women of the South in War Times, Ed.

Mathew Page Andrews, Baltimore, 1920, pp. 178-179.

[6] New York Times, 16 Oct 1862, p. 1; and “Chantilly Fairfax

County,” Alexandria Gazette, 15 Mar 1863, p. 1. Article

explains that there was a misconception that Chantilly

was the property of General J.E.B. Stuart.

[7] “Died,” Alexandria Gazette, 05 September 1846, p. 2.

[8]

“Reward,” Alexandria Gazette, 08 January 1855, p. 2.

[9] Alexandria Gazette, 15 Jan 1855, p. 2.

[10]

“Communications,” Alexandria Gazette, 29 Jan 1861, p. 2.

[11]

Official Records of the Civil War, 1 Sept 1862, Report Written January 15,

1863, Chap XXXI, p. 1010.

[12] Alexandria Gazette, 19 Feb 1863, p. 2.

[13] New York Times, 16 Oct 1862, p. 1.

[14]

Official Records of the Civil War, 24 October 1862, Chapter XXXI, p. 478.

[15]

Official Records of the Civil War, 22 October 1862, Chapter XXXI, p. 468; and New York Times, 11 Dec 1862, p. 1v.

[16]

Official Records of the Civil War, 29 November 1862, 30 November 1862, and 01

December 1862, Chapter XXXIII, pp. 17 – 19.

[17]

Official Records of the Civil War, 23 March 1863, 26 March 1863, and 07 April

1863, Chapter XXXVII, pp. 70-73.

[18]

Official Records of the Civil War, Chapter XLI, p. 4.

[19] Alexandria Gazette, 05 Mar 1863, p. 1.

[20] Mrs.

McGuire, “Diary of Mrs. McGuire,” in The Women of the South in War Times, Ed.

Mathew Page Andrews, Baltimore, 1920, pp. 178-179.

[21] FX DB K4(89):146, 29 November 1865; FX DB Y4(103):58, 29 May 1879.

[22] Fairfax County Chancery Case CFF 75bb, 1887.

[23] Fairfax County

Superior Court Book, 24 Nov 1846, p. 143.

[24] Mrs.

McGuire, “Diary of Mrs. McGuire,” in The Women of the South in War Times, Ed.

Mathew Page Andrews, Baltimore, 1920, pp. 178-179.

[25] Fairfax County Chancery Case CFF 75bb, 1887.

Also Chantilly Plantation Stone House research notes by Susan Hellman, Fairfax

County Department of Planning and Zoning, October 2006.

[26] FX DB G5(111):419, 12 Jan 1888.

[27] FX DB

410:363, 28 Jun 1943.

[28] FX DB

2484:142, 20 Jul 1964.

[29] FX DB

2918:619, 15 July 1967.

[30] Dranesville Dist. Map, G. M. Hopkins, 1878.

| |