| Spindle Sears House Centreville, Virginia Built 1934 |

|

by Debbie Robison June 16, 2008 |

| INTRODUCTION |

|

Partially Restored Spindle Sears House, 2007 During the Great Depression,

Roger Spindle, who had a stable job as a mail supervisor with the |

| SPINDLE EARLY YEARS |

|

Roger Bradshaw Spindle grew up in

the Centreville area, where he was editor of the Centreville News, a

publication of the In the first issue of the

Centreville News, the front page story discusses the significance of the

proposed new concrete road known as |

|

Once our little town was the metropolis of |

|

Following graduation from high

school, Spindle attended business school ( Due in part to the construction

of the concrete |

| THE GREAT DEPRESSION AND THE NEW DEAL |

|

During the Depression, Roger Bradshaw Spindle and Wilma Geneva Spindle purchased the 4 �� acre parcel, and constructed a Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog house.[4]

When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president in 1933, he enacted New Deal legislation during a special congressional session to improve the economy and create jobs. One of the Acts passed during this �Hundred days� session was the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act of 1933. The act provided $200 million to farmers to refinance mortgages and provide funds.[5]

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Photo Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Sears, Roebuck & Company (Sears) had an economic stake in the success of New Deal programs. The Depression caused prices, including those in Sears catalogs, to fall as wages and the number of wage earners declined. Prices in the Winter �33/�34 catalog were lower than prices in the 1930 and 1931 catalogs. In the Spring/Summer 1933 catalog, Sears pledged to work for relief. |

|

We pledge the support of this company, unreservedly and wholeheartedly,

to |

|

Six months later, Sears president R E Wood wrote to describe the companies efforts. |

|

�we have worked with government, agricultural, Today, agriculture is on its way up. Farm prices have definitely risen.

Hand in hand with this advance has come a corresponding recovery in |

|

Henry A. Wallace, Secretary of

the Department of Agriculture at the time, responded to the Sears pledge in a |

|

The pledge of support by Sears, Roebuck and Company to sound agriculture relief is a positive affirmation of the interests of business, and particularly your business, in the prosperity of farmers. Their expression is gratifying proof that if the Agricultural Adjustment Act can be worked out as we hope, the Department may be sure of fine cooperation of men high in the business world. |

|

In the Winter �33/�34 catalog, Sears explains how the success of New Deal programs has caused prices to increase over the spring catalog prices. |

|

THE NEW DEAL�THE NEW CATALOG These are history-making days � days in

which all Designed primarily for the benefit of the farmer and the wage earner, the vast program of national recovery has gone steadily forward. As it has progressed, prices have risen. |

|

On Twenty-three days later, the Spindle�s purchased the Centreville lot consisting of 4-1/2 acres from Paul and Elizabeth Rector for $800.00.[7] |

| PURCHASE AND CONSTRUCTION |

|

Roger Spindle, who enjoyed Sears,

Roebuck and Co. catalog shopping, opted to build a kit home close to family.

When selecting plans for the construction of their home, the Spindle�s chose

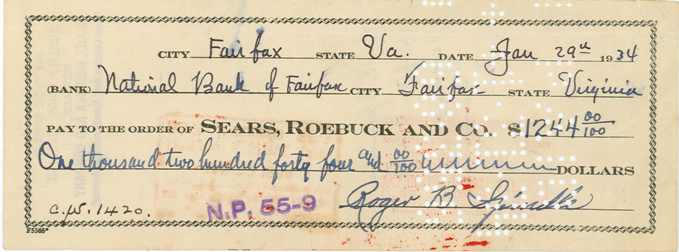

the The amount paid by Roger Spindle was $1,244.00. Perhaps this sum included the garage, appliances, wallpaper, the furnace, etc.

|

|

Check issued by Roger Spindle to purchase the kit house from Sears, Courtesy Priscilla "Susan" Spindle Mosier |

|

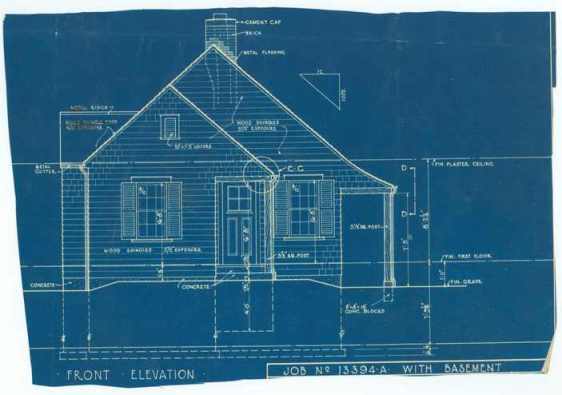

The building materials were

purchased from Sears and shipped by railroad to the Some of the materials may have been purchased locally, such as the cement used to form the walls of the basement that Roger Spindle had dug out.[12] The front of the house was

constructed to face

|

|

Blueprint for an elevation of the house, Courtesy Priscilla "Susan" Spindle Mosier

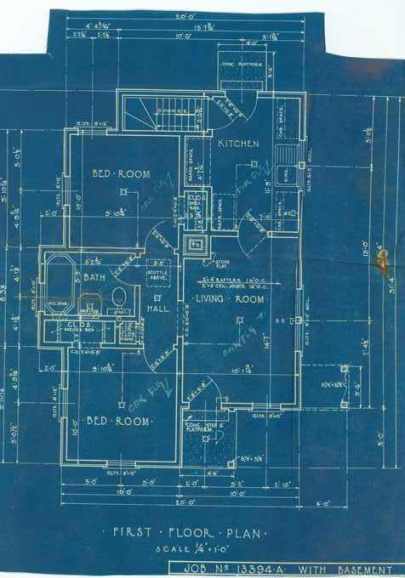

Blueprint for the floorplan of the house, Courtesy Priscilla "Susan" Spindle Mosier |

|

Susan Spindle Mosier, who grew up in the house, recollected that her parents made many changes to the interior wall coverings and paints. Most of the interior walls and ceilings of the house were wallpapered. Wilma Spindle often repapered the house, and it was a family activity. At one time, the front bedroom had a lilac floral and striped wallpaper, the living room had a tan paper, and the ceilings of the bedrooms and living room were covered with a white paper. The kitchen was at one time painted light green. The bathroom was painted many times in different colors, and the cabinets were painted blue.[13] Red and tan checkered linoleum flooring covered the wood floors in the kitchen and bathroom. Both the kitchen and bathroom wood floors were composed of fir, rather than oak, which was used in the rest of the house. The existing red Formica countertop was installed in the 1950s. Previously, the counter top was likely wood. The base and wall cabinets in the kitchen are original. The top left cabinet held the dishes, and the top right cabinet held the hard to reach candies and cookies. When Susan Spindle Mosier was little, she would climb up on the counter to try to reach the cabinet, but never could because it was above the refrigerator. The base cabinets held pots and pans, and the cabinet under the sink held cleaning products.[14] Originally, the house was heated

with a coal-fired furnace. Coal was stored in the basement in a bin beneath a

window. The basement concrete slab did not extend into the area of the coal

bin. Later the house was heated with an oil-fired furnace. The fuel-oil tank

was located beneath the dining room. The Pull shades, which likely came with the house, were installed on all of the windows. These were later replaced with Venetian blinds. The house did not have air conditioning until after Roger Spindle died in 1965. A window air-conditioning unit was installed in the living room window adjacent to the front door.[15] The house had electric outlets, lights, and appliances installed at time of original construction. The refrigerator and the stove, which was located in the niche opposite the sink, were powered by electricity. Some of the light fixtures in the house may have been replacements. The metal base of the light fixture in the front bedroom was stamped on the inside with the brand Homart, owned by the Dornback Hardware and Plumbing Company. Dornback began supplying fixtures to Sears under this brand in the late 1940s. The exterior light socket, made of porcelain, had Woodwin stamped on the inside. The three sockets on the kitchen light fixture, made of plastic, were also stamped with the Woodwin brand. �� A push-button for an Initially, water for the house was pumped from the springhouse, requiring that the springhouse be occasionally cleaned out. A pump was located in the basement. Due to the effort required to clean out the springhouse, a well was dug in the yard after Roger Spindle Sr.�s death. The pump in the basement then became obsolete. The Spindles did not have a hot water heater until after World War II. Until that time, water was heated on the stove.[17] |

| Springhouse |

|

Waste disposal from the bathroom was directed into a leech field to the side of the house beyond the garage. In the mid-to-late 1950s, a new field was dug. It is unknown if the new septic field was built in the same location. Dish water was tossed outside, or used to water the flower garden. Garbage was burned in the backyard until the dump was established.[18] The exterior house color scheme

was originally gray and white: The wood wall shingles were painted gray, and

the trim painted white. The stoop was painted gray, and then red. A white gate,

no longer extant, was situated between two posts located under the curved roof

line. The Herndon Observer newspaper

reported on the progress of the construction. On |

|

Mr. Roger Spindle has purchased a lot in Centreville and is preparing to build a home there in the near future.[20] |

|

By March 22nd the foundation work on the house was progressing rapidly.[21] Construction took about 2-1/2 months. In May of 1934, the Herndon Observer reported that Mr. Roger Spindle�s pretty bungalow is nearing completion.[22] �and Mrs. Roger Spindle�s bungalow is almost ready for occupancy.[23] In the fall of following year, Roger Spindle had his lawn graded.[24] � Spindle House, January 1939, Courtesy Priscilla "Susan" Spindle Mosier |

|

The house and grounds were used

for several functions. Wilma Spindle, and her daughter

The Spindle�s may have constructed their garage at the same time the house was built; certainly by 1937 when the garage was photographed by USDA aerial photographers. Though the garage is no longer extant, the structure was photographed when the Spindle�s lived at the house. The garage doors shown in photos were available in the Winter �33/�34 catalog. The garage was constructed with metal sheathing over a wood frame. The roof may have originally had red shingles.[27] Though the garage was sufficient

for the first automobile used by Roger Spindle to commute down

Wilma Spindle in front of garage, ca. 1965, Courtesy Priscilla "Susan" Spindle Mosier |

|

Roger Spindle drove to work each

day until he retired in 1961. It took him about an hour to drive to Most of the grocery shopping was

done in The children walked to The garage was |

| UTILITY SERVICES |

|

The Alexandria Light & Power

Company, which built a large substation in On October 22, 1932, the During the �New Deal Era�

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed executive order no. 7037, which

established the Rural Electrification Act (REA). The REA allocated 100 million

dollars to ensure that electricity was provided to rural

Privately owned electric companies started to notice that there was a profit to be made in rural areas, and started to build �spite lines� in wealthier rural areas that were close, and sometimes within, a cooperative service area. Building �spite lines� gave private companies a greater opportunity to turn a profit. The private companies knew that cooperatives needed wealthier customers to offset the cost of providing electricity to poorer customers and to areas that were not highly populated. Electricity was available when the Spindle Sears House was constructed. Priscilla �Susan� Spindle Mosier noted that the family�s electric provider was Virginia Electric and Power Company (VEPCO), which absorbed the Virginia Public Service Company in June 1944.[38] In 1932, Paul Rector and his wife

The Spindles granted an easement

to the

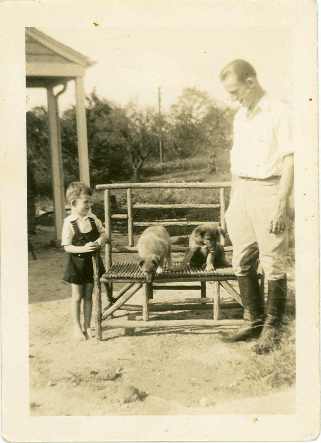

Roger Spindle Sr. and Roger Spindle Jr. with utility pole in background, 1935, Courtesy Priscilla "Susan" Spindle Mosier |

| ENDNOTES |

|

[1] [2] Herndon

Observer, [3] [4] FXDB

J11(270):374, [5] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/trouble/timeline/

and http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_043900_hundreddays.htm

viewed 5 January 2006 [6] [7] FX DB J11(270):374 [8] [9] [10] FX DB M11(273):4 [11] [12] [13] [14] Ibid. [15] Ibid. [16] Ibid. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid. [19] Ibid. [20] Herndon

Observer, [21] Herndon

Observer, [22] Herndon

Observer, [23] Herndon

Observer, [24] Herndon

Observer, [25] [26] Ibid. [27] Ibid. [28] Ibid. [29] Ibid. [30] Ibid. [31] Ibid. [32] Ibid. [33] The [34] The [35] Herndon

[36] [37] FXDB F11(266):133, 28 November 1932. [38] [39] FXDB C11(263):129, 11 April, 1932. |