Naval Captain Andrew Fitzhugh

of Oakhill

(near Annandale, Virginia) |

|

|

Back in the age of naval sailing ships, Andrew Fitzhugh of

Oak Hill advanced through the officer ranks and reached the pinnacle of his

career as a naval captain during the Mexican-American war in command of the

steam frigate Mississippi.[1]

The Mexican-American war was caused by a dispute between the United Mexican

States and the United States of America over the ownership of land between the

Rio Grande and the Nueces River. Fitzhugh’s spotlight in history occurred at

the start of the war when he announced the blockade of the port of Vera Cruz.

Back in the age of naval sailing ships, Andrew Fitzhugh of

Oak Hill advanced through the officer ranks and reached the pinnacle of his

career as a naval captain during the Mexican-American war in command of the

steam frigate Mississippi.[1]

The Mexican-American war was caused by a dispute between the United Mexican

States and the United States of America over the ownership of land between the

Rio Grande and the Nueces River. Fitzhugh’s spotlight in history occurred at

the start of the war when he announced the blockade of the port of Vera Cruz.

Oakhill, family home of Andrew Fitzhugh

Fitzhugh was described as a corpulent man. Reverend Fitch W. Taylor, sailing aboard the Home Squadron

flagship, gave a more generous account.

|

|

Captain Fitzhugh of the Mississippi is a gentleman of comfortable proportions for wintery weather;

and enjoys a flow of spirits with good nature, that loves to laugh, and to make

others laugh. He amused me, by recounting an adventure with one of my clerical acquaintances;

and professes to have been quite liberal, and is yet quite favorable towards

Bishop Meade’s “Manufactory of Parsons” as he designates the Episcopal

Seminary, near Alexandria, D. C. [2]

|

The Mississippi was

a ten gun frigate equipped with a coal-fired steam engine that drove paddle

wheels positioned on each side of the hull. The vessel was also rigged for sail

as an alternate source of propulsion, which was advantageous in the event of a

coal shortage.

The Mississippi was

a ten gun frigate equipped with a coal-fired steam engine that drove paddle

wheels positioned on each side of the hull. The vessel was also rigged for sail

as an alternate source of propulsion, which was advantageous in the event of a

coal shortage.

Sketch of the frigate steamer Mississippi when it was part of the Japanese Squadron, from Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 1853

|

|

|

Fitzhugh learned that hostilities

commenced on the part of the Mexicans via correspondence received on May 4,

1846 while he as in Pensacola Bay. He immediately proceeded to Vera Cruz,

Mexico per the orders of Commodore David Connor who commanded the Home Squadron

that operated in the Gulf of Mexico.[3]

Shortly after arriving, Fitzhugh notified the commanders of neutral vessels in

the harbor of Vera Cruz of a blockade of that port.

|

|

STEAMER MISSISSIPPI, May 20, 1846. Sir: - I have the honor to inform you that the port

of Vera Cruz was this day blockaded by the Naval forces of the United States

upon this station. Neutral vessels now in the harbor are at liberty to leave,

with or without cargo, within the space of fifteen days from the present date.

Mail-packets, not merchantmen, belonging to neutral Powers, are at liberty to

enter and leave the port. I remain, with respect, &c. ANDREW FITZHUGH. [4]

|

|

To this notice the editors of the Mexican journal El

Indicator responded:

|

|

And are we to remain calmly looking on seeing the

hated flag of the stars waving in the breeze? Shall we be citizens less worthy

than those of Matamoras, whose heroic valor will be spoken of as an immortal

example of bravery? No! a thousand times no! And be he a thousand times cursed

who, in such a trying time as this, abandons his post on the walls of heroic

Vera Cruz! [5]

|

|

The El Indicator called on the government to arm every one

of their vessels as privateers and to give letters of marque to any Mexican who

asks for them.[6]

Fitzhugh returned to Pensacola the following month bringing

as passengers Dr. Wood, U.S. Navy, who was the bearer of important dispatches

from Commodore Sloan, commanding officer of the naval forces in the Pacific,

John Parrot, U. S. consul at Mazatlan, Mr. Diamond, U. S. consul at Vera Cruz,

and seven other passengers.[7]

This was not the first time that Fitzhugh ferried passengers between Mexico and

the United States. Shortly before the war, Fitzhugh conveyed John Slidell, the

United States Minister to Mexico, back to the U.S. In a letter found in a box

under the attic floor boards at Oakhill, Slidell thanked Fitzhugh for bringing

him home in Fitzhugh’s gun boat. He suggested that he had reason to believe

that the President would send an important message to Congress on the Mexican

situation shortly.[8]

|

|

Fitzhugh returned to Vera Cruz with the Mississippi and was on hand when an attempt was made to cut out

several small Mexican vessels from the river Alvarado. On July 28, 1846, the

flagship Cumberland, with support

vessels in her wake, was underway towards the mouth of the Alvarado. Commodore

Connor mistook the point of passage through the reefs at the Point of Lizardo

and ordered the ship to tack causing the ship to hit the coral. Wind and the

tide drove the ship further on. Attempts to take the ship beyond the shoal

tended only to place the ship further upon the reef. The ship came to a dead stop,

and the rise and fall of the sea swell succeeded in wedging the keel two or

three feet down into the reef.

Fitzhugh returned to Vera Cruz with the Mississippi and was on hand when an attempt was made to cut out

several small Mexican vessels from the river Alvarado. On July 28, 1846, the

flagship Cumberland, with support

vessels in her wake, was underway towards the mouth of the Alvarado. Commodore

Connor mistook the point of passage through the reefs at the Point of Lizardo

and ordered the ship to tack causing the ship to hit the coral. Wind and the

tide drove the ship further on. Attempts to take the ship beyond the shoal

tended only to place the ship further upon the reef. The ship came to a dead stop,

and the rise and fall of the sea swell succeeded in wedging the keel two or

three feet down into the reef.

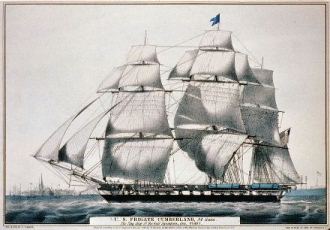

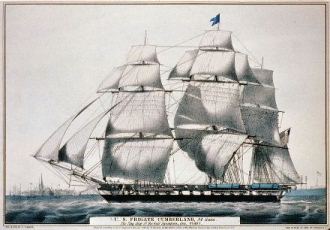

USS Cumberland, Flagship of the Gulf Squadron, Currier & Ives Print, ca. 1848.

The steamer Mississippi, left at anchor off Green Island, was called to assist. The Cumberland, still in sight of Green

Island signaled the Mississippi to

come and tug the ship off the reef. The operation began the following day when

daylight would make for a safer operation. A hawser (thick rope for towing or

mooring a ship) was put aboard the Mississippi,

but moments after the tugging began, the hawser snapped. After considering the

next move, a light chain cable was conveyed out to the Mississippi by the Cumberland’s

launch. This caused some concern since the Mississippi’s

sister ship, the steamer Missouri,

sank in the Potomac River while attempting to take a ketch off an oyster bed

using a heavy chain.

Once the chain cable and additional hawsers were passed

through the hawser-holes in the bow of the frigate Cumberland, they were attached to the stern of the Mississippi. A call of “All’s fast, Sir”

followed by a return reply of “Haul tight!” was all that could be heard. The paddle

wheels of the steamer started churning while black smoke poured out from the

chimney pipe. The chain cable held but there was no movement off the reef.

Fitzhugh sent a message to Commodore Connor that He was doing his best.

The Cumberland

began to further lighten its load. During the night, they had pumped thousands of

gallons of water overboard. Now they dumped 16 guns from the upper deck into

the sea and made rafts out of the spare spars and anchored them to the reef.

The shot, round, grape, and canister was sent on board other ships along with

provisions of beef and pork. And still the Cumberland

was stuck.

The Mississippi

remained at its labors for the entire day making very slight progress to rotate

the ship. Inexplicably, Commodore Connor gave up hope and exclaimed to the

captain, “Come Forrest, it is in vain – let us take it quietly – and now get a

cup of tea.” They proceeded to the table in the cabin where the Commodore

added, “the Department shall be informed, Captain Forrest, that it was no fault

of yours, that the ship went ashore.” Captain Forrest soon left the table and

went on deck. It wasn’t long before half a dozen voices yelled “She is afloat!”

“Stand by to let go the larboard anchor!” ordered Captain

Forrest. The Commodore, still seated at the table heard the order, sprang to

his feet and raced to the upper deck clapping his hands and exclaiming, “Thank

God, she’s off! Thank God, she’s off!” The Mississippi

lurched forward with the Cumberland

in tow until she reached the length of her cable. In total, the Cumberland was stuck

on the reef for 27 hours. The following day Fitzhugh towed the Cumberland further from the reef. It

took only a few days for the crews to retrieve the guns and spars from the reef.[9]

|

|

|

Another attempt was made to capture Mexican vessels in the

Alvarado port. Captain Fitzhugh with the Mississippi,

along with the Princeton and three

small schooners, were sent to cut out the vessels, i.e. go in and snatch them. At

least one schooner anchored close to the shore battery and began firing. The

steamers were out of range, but subsequently the Mississippi came close enough.

The Mississippi commenced

firing but could not spring the ship due to the strong current. (Springing a

ship involved attaching a rope to the anchor cable at the bow and taking it up

aft by the capstan. This allowed the ship swing left or right to bring the guns

to bear.) As a result, Fitzhugh could only use his bow guns. Because of the

strong current and the shoal water on the bar, the boat expedition could not be

sent into the river.

Firing continued until the dark. It was expected that they

would recommence the following morning, but Commodore Connor signaled “come

here again,” which ended their first fire on the enemy. No damage was done to

the steamers or schooners; however no advantage was gained by the affair

either.[10]

Commodore Connor was criticized in publications for not taking

more aggressive action in the Gulf.[11]

The Navy Department sent Commodore Perry to support Connor. Perry relieved

Fitzhugh of his command of the Mississippi when Fitzhugh was given command of

the navy yard at Pensacola.[12]

|

|

|

Andrew Fitzhugh (1793-1850) grew up at the family home of

Oakhill located near present-day Annandale, Virginia. He became a midshipman in

June 1811 at the dawn of the War of 1812 and was promoted to lieutenant five

years later.[13]

As a 4th lieutenant, he served on the 38-gun frigate Congress and toured the West Indies to

protect United States commerce from pirates.[14]

The 1st lieutenant onboard the Congress

was John D. Sloat who later became commodore of the Pacific Squadron during the

Mexican-American war.

In 1825, Lieutenant Fitzhugh was attached to the 74-gun ship

of the line North Carolina for their

28 month cruise of the Mediterranean. During this time, the North Carolina served as the flagship for

commodore John Rogers.[15]

Fitzhugh remained attached to the North

Carolina serving under Master Commandant Mathew C. Perry, who later became

commodore of the Gulf Squadron during the Mexican-American war.[16]

In 1829, Fitzhugh served on the U.S. ship

St. Louis under Captain Sloat whom he

served with on the Congress. The St. Louis was a sloop of war.

In 1829, Fitzhugh served on the U.S. ship

St. Louis under Captain Sloat whom he

served with on the Congress. The St. Louis was a sloop of war.

Sloop of War St. Louis

In 1831, Fitzhugh was lieutenant commandant of the schooner Dolphin armed with twelve 6-pounder

guns.

|

|

[1] Alexandria Gazette, 15 May 1846, p. 2.

[2] Taylor,

Rev. Fitch W., The Broad Pennant, or A

Cruise in the United States Flagship of the Gulf Squadron, During the Mexican

Difficulties; Together with Sketches of the Mexican War, from the Commencement

of Hostilities to the Capture of the City of Mexico, Leavitt, Trow &

Co., New York, 1848, p. 228.

[3] Boston Courier, 18 May 1846, p. 1.

[4] Washington Reporter (Washington PA), 20

Jun 1846, p. 1.

[5] Daily Union (DC), 11 Jun 1846, p. 3.

[6] Daily Union (DC), 11 Jun 1846, p. 3.

[7] Auburn Journal and Advertiser (Auburn

NY), 17 Jun 1846, p. 3.

[8]

Howrey, Mrs. Edward F., “Oak Hill,” History

of Fairfax County, Virginia, Inc., Vol. 7, 1960-1961, Independent Printers,

Vienna, 1961, p. 35.

[9] Taylor,

Rev. Fitch W., The Broad Pennant, or A

Cruise in the United States Flagship of the Gulf Squadron, During the Mexican

Difficulties; Together with Sketches of the Mexican War, from the Commencement

of Hostilities to the Capture of the City of Mexico, Leavitt, Trow &

Co., New York, 1848, pp. 240-247; Also, 02 Sep 1846 True American (Lexington

KY), p 3.

[10] Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), 22 Aug 1846, p. 2.

[11] North American (Philadelphia), 30 Oct

1846, p. 1.

[12] Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), 04 Sep 1846, p. 2. ; Also, Daily Union (DC), 29 Sep 1846, p. 3.

[14] Baltimore Patriot, 05 Nov 1822, p. 2, Newburyport Herald (MA), 19 Nov 1822,

p2.

[15] Charleston

Courier (Charleston, SC),

31 Mar 1825, p. 2.

[16] Pensacola

Gazette (Pensacola, FL), 24

Aug 1827, p. 2.

|

Fitzhugh returned to Vera Cruz with the Mississippi and was on hand when an attempt was made to cut out

several small Mexican vessels from the river Alvarado. On July 28, 1846, the

flagship Cumberland, with support

vessels in her wake, was underway towards the mouth of the Alvarado. Commodore

Connor mistook the point of passage through the reefs at the Point of Lizardo

and ordered the ship to tack causing the ship to hit the coral. Wind and the

tide drove the ship further on. Attempts to take the ship beyond the shoal

tended only to place the ship further upon the reef. The ship came to a dead stop,

and the rise and fall of the sea swell succeeded in wedging the keel two or

three feet down into the reef.

Fitzhugh returned to Vera Cruz with the Mississippi and was on hand when an attempt was made to cut out

several small Mexican vessels from the river Alvarado. On July 28, 1846, the

flagship Cumberland, with support

vessels in her wake, was underway towards the mouth of the Alvarado. Commodore

Connor mistook the point of passage through the reefs at the Point of Lizardo

and ordered the ship to tack causing the ship to hit the coral. Wind and the

tide drove the ship further on. Attempts to take the ship beyond the shoal

tended only to place the ship further upon the reef. The ship came to a dead stop,

and the rise and fall of the sea swell succeeded in wedging the keel two or

three feet down into the reef.

In 1829, Fitzhugh served on the U.S. ship

In 1829, Fitzhugh served on the U.S. ship