| Chestnut Hill |

|

by Debbie Robison November 2003 |

|

[Note: The following is an

excerpt. The full graphic-laden report Chestnut Hill, A Preliminary Structure

Report may be reviewed at the Thomas Balch Library in |

| INTRODUCTION |

| Location |

Chestnut Hill is located at Chestnut Hill is located at

|

|

The house and outbuildings are

situated three-fourths the way up a hillock, part of the |

| Method |

|

This preliminary structure report

was prepared as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Historical

Archaeology HIS-180 course offered by |

| Primary source records, including deeds, will, chancery, and tax records, etc., were researched at the Loudoun County Courthouse, the Thomas Balch Library, and other locations. Two site visits were conducted; the first concentrating on the mansion interior and the second on the site, outbuildings, and extant features. |

|

The deed and will research was

successful, and yielded a chain of title back to the northern neck grant for the

property. Tax records were researched to determine construction dates. Since

construction was completed prior to 1820 when |

| HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION |

| Indian Settlements |

|

In a region along the Potomac

River that would one day be settled by colonists, Franz Louis Michel traversed and mapped

the area in 1707, depicting on his map an Indian long house in |

|

Proprietor’s land grants in the

area used Indian landmarks in survey descriptions. The meets and bounds of

Francis Awbrey’s 1728 patent along the |

|

The grave was located near the |

| Area Colonial Settlements |

|

Thomas Albin, Samuel Thacker, and

William King obtained the earliest Proprietor’s land grant in the area east of

the Catoctin Mountains and north of |

|

The fertile land along the river was the first to be granted, primarily to

tidewater area land speculators who established quarters there. The earliest

known area resident was a man named John Tuton who was already living as a

squatter on land in 1728 when Awbrey obtained his patent, a point of which

terminates “ near the place where John Tuton lives on.” By 1742, Tuton no longer

lived there.[5] |

|

William Hawlin was another early

grantee along the |

|

The Sinclair family lived near one

another on land that would one day encompass the Chestnut Hill tract. John

Sinclair, possibly Margaret’s son, was granted a tract nearby on the |

| The Great Awakening |

|

During a period of religious

resurgence, termed “ The Great Awakening” by historians, many Pennsylvanians

emigrated to the region in search of land to farm in an area where they could

worship according to their own beliefs. Historians frequently acknowledge the

immigration of the Quakers to |

|

Many Baptists organized to move to

northern Loudoun, and once here, they built a meeting house called |

|

New Valley Baptist Meeting House,

currently a residence, is located on the |

|

William Jones, a Baptist from

|

|

For a brief period of three years,

John Trammell owned many of the Sinclair family tracts of land.[21]

He subsequently sold the land to William Jones, who acquired seven tracts of

land from 1761 to 1770 totaling over 1,430 acres.[22]

Most of the tracts were purchased in 1761. In 1762, Jones was granted a patent

for 136 acres of land 2 miles south the tract of land that would one day be

called Chestnut Hill. Jones was still living on the patented tract at his death.

In his will he states that he “ leaves to his loving Wife the use of the

plantation I live on…”[23] |

|

In contrast with the Quakers,

William Jones, was also a slave owner. He also bequeaths to his wife, after

bequeathing three cows and before bequeathing half of his hogs, “ a Negro Wench” and “ a Servant Man Calld

Rowland”. In addition to devising land to his two sons, Jones bequeaths his

brass kettle and wearing apparel to Joshua and his watch to James. To Joseph

Thomas, Minister and William Lewis and Thomas George, elders of New Valley

Meeting, he bequeaths “ a piece of land containing 1-1/2 acres whereon the

baptist Meeting House is Built. Joyning this |

|

Another Pennsylvanian who likely

was a member of the New Valley Meeting was Leonard Ansell. He purchased land

from William Jones paying with Pennsylvanian currency.[25]

His daughter, Margaret Fry, was buried in the New Valley Meeting House

cemetery.[26] |

|

One year before his death, Jones

sold 519 acres to fellow New Valley Meeting church elder Thomas George, though

evidence suggests that George had established a tenant farm on the property

several years earlier.[27]

|

| George Leasehold & Ownership (ca. 17661779) |

|

It is hypothesized that Thomas

George built a stucco-covered two-story stone house ca. 1766 prior to purchasing

the land.[28]

This building, comprising the earliest section of the current Chestnut Hill

home, exhibits the character of a 1760s Pennsylvania-German house.[29]

|

|

Items listed in George’s probate

inventory suggest he may have been a carpenter and cooper. Included were “ Seven

Augers, Three Saws, One Adz and three Axes, one set of Cooper Tools, Sundry

Files, four Gauges and twelve Chizels, One Glue Pot with several Pools, Two

drawing knives, two Hammers, eleven plains, cross cut-saw and froe, coopers

hoops and rake.” The inventory also lists three additional slaves, Frank, Halis,

and Pat. [30]

The inventory suggests that Thomas George, or his grown son, William George who

was living with him at the time, may have been personally involved in the

construction of the Chestnut Hill home and provides a record of what tools may

have been used to build the house. |

|

Elder George held the land for 9

1/2 years before he sold 200 acres, including, presumably, the stone house, to

Josias Clapham in 1779. George’s will, written in 1787 and proved in 1798, left

one guinea to his son, William, and devised to his three sons-in-laws, brothers

Isaac, John and Joseph Steers, the slaves and the remainder of his estate.

George provides another example of a pious Baptist owning slaves. He owned a

“ negro Wench |

|

Fifty years later, the property

was still being called “ The George Tract” in addition to the Chestnut Hill

name.[32] |

| Josias Clapham Ownership (1779-1803) |

|

During the Revolutionary War,

Colonel Josias Clapham purchased 200 acres of land on which it is presumed stood

by that time the small Chestnut Hill house.[33]

His uncle, of the same name, had owned land in the area since obtaining a land

grant in 1739.[34]

Clapham also purchased an adjacent 150-acre parcel from Anthony Haynes on 12 May

1772,[35]

as well as the furnace mountain parcel he bought in partnership with four

Johnson brothers to build an iron furnace.[36]

Clapham operated several ventures: a water mill, warehouse, and mercantile.

|

|

The Chestnut Hill house may have

been expanded during the ownership of Josias Clapham. A two-story stone addition

was added to the north facade of the original building. It is conceivable that a

man of Clapham’s means, with a wife and three children, would live in a house

larger than two rooms. Physical evidence supports a date of construction during

the end of Josias Clapham’s ownership period or the early part of his son’s

ownership.[37] |

|

A survey plat dated 7 September

1834 depicts ten structures in the area of the dwelling house, most of which are

located just on the other side of the adjacent property line. Their spacial

relationships suggest that they are associated with the house. Since Josias

Clapham was the first person to own both parcels, it can by hypothesized that

many of these outbuildings were built during the Clapham ownership period.[38]

|

|

Upon his death in 1803, he willed

the property including the house where he lived to his wife, Sarah, for use

during her lifetime, after which the property would revert to their son, Samuel

Clapham.[39]

|

| Samuel Clapham Ownership (1803-1826) |

|

Samuel Clapham did not succeed in

business as his father did. Clapham sold off portions of the land devised to him

by his father and took out loans putting the remaining property up for

collateral in trust agreements. When asked his opinion of Samuel Clapham’s

business management practices, an acquaintance stated that “ he was very much the

reverse of a man of Judgment in the management of his affairs. he was neither

prudent, or thrifty, but in my estimation, imprudent, thriftless, hasty and

inconsiderate.”[40]

|

|

Clapham traveled to |

|

Notes were yielding a higher

percentage interest in |

|

Samuel Clapham and his wife

|

|

Regardless, Clapham more than

doubled the size of his dwelling house. The large two and one half story stone

addition, which was covered in stucco, required a great deal of lime for

construction. In 1819, Clapham entered into an agreement with John Barrett to

purchase Clapham’s lime kiln on the |

|

In 1833, the Clapham dwelling

house was described as “ very large…there are at least ten rooms in it, if not

eleven.” The value of the house was set at “ twenty five hundred or two thousand

dollars.”[44]

As early as 1826, the “ Mansion House and farm” was called Chestnut Hill.[45] |

|

Towards the end of his life,

Samuel Clapham entered into a deed of trust with Richard Henderson and Thomson

F. Mason, a nephew by marriage, to transfer control of the management of his

estate due to the fact that “ the declining health of the said Samuel renders him

unable to attend to the Management and sale of his estate and to the payments of

his Debts.”[46]

His obituary appeared in the Whig Obituaries on 19 September 1826.[47]

|

| Elizabeth Clapham Ownership (18261833) |

| For six years, with the assistance of her niece’s husband, Thomson F. Mason, Elizabeth Clapham, the widow of Samuel, managed her estate. She was encumbered by her deceased husband’s debts yet took control of the businesses to increase her revenues. On April 26, 1828, Elizabeth Clapham placed an advertisement in a Leesburg newspaper headed: |

| To Millers, Farmers, Mechanics,

and enterprising men of every description Look Here![48] |

|

Despite her efforts, she was

unable to meet the debt obligations and her home, Chestnut Hill, along with the

mill and other properties, was put up for auction in front of the Leesburg

courthouse by trustee James W. Ford. Elizabeth Clapham was the highest bidder

and paid eleven thousand five hundred dollars. On 8 December 1827, as a result

of a suit brought by the representatives of William Gregg. An advertisement

announcing a trust sale for a tract of land was placed in the newspaper on 5

November 1827. A dispute was voiced during the auction by Thomson F. Mason who

alleged that he held an earlier note that was secured by the land and that

whoever purchased the property at auction may have legal action brought against

them. To resolve the dispute, several gentlemen accompanied Mr. Mason to the

Clerk’s office to search the deed records. Upon finding that Mason did hold an

earlier deed, the auction continued. Bidding lasted for over an hour, yet Mason

had the high bid of only $2,000, which the Chatham Fire Insurance executives

claimed was low because of alleged threats Mason made at the bidding. Mason was

bidding on behalf of Elizabeth Clapham in whose name the property was

transferred. The Chatham Fire Insurance Company filed suit in 1833 against

Samuel Clapham’s administrators due to default on their note and not having

recourse in collateral because the property was sold to Elizabeth Clapham in

1828.[49] |

| George Price / Elizabeth Clapham Price Ownership (18331839) |

|

Elizabeth Clapham married George

Price on 30 January 1832.[50]

Price acquired a life estate in the Chestnut Hill tract in an “ anti nuptial”

(pre-nuptial) understanding between himself and Richard H. Henderson who was a

trustee of the property.[51]

He sold the property on 16 October 1839 to his wife’s niece, |

| Mason Family Ownership (18391930) |

|

Elizabeth Clapham Price Mason, known as Betsey, owned the property

for thirty-four years until her death in 1873. During a portion of that time,

she maintained her residence in |

|

Oral history purports that the

house was not burned following Union orders to do so because of the respect the

officer in charge of carrying out the orders had for the Mason name. In

addition, it is believed that an original copy of the Virginia Declaration of

Rights was housed at Chestnut Hill during the Mason family ownership period

until it was sold to the National Archives in 1930.[54] |

|

Betsey willed the property to her

son, Dr. J. Francis Mason in 1873.[55]

He and his wife |

|

During Thomson F. Mason’s

ownership, he struggled with debts and frequently used the Chestnut Hill land as

loan collateral, as well as personal property located at Chestnut Hill such as

the |

| Gore Ownership (19301973) |

|

Lucy Gore and her husband, Coleman

C. Gore added modern heating, plumbing, and wiring to the house. A new closet

and new stairs to the basement were also installed.[59]

In addition, the stucco façade was removed to reveal the stone exterior walls.[60]

Mrs. Gore canned food for storage in the cellar. Some of the canned food remains

today. |

| Coleman Gore was the uncle of Vice President Al Gore. Discovered in the attic by the next owners was a photo of a young Coleman Gore with his younger brother, Senator Albert Gore Sr., and their sister. |

|

The Gore’s lived in the house

until about 1957, after which it sat vacant until purchased by Alton C. Echols

in 1973.[61]

Lucy Gore’s writing desk was sold with the house. |

| Echols Ownership (19732003) |

|

Following his purchase, Echols

conducted extensive renovations to both the house and grounds adding boxwoods to

the landscaping. He placed the property up for auction in 1987; however, he did

not sell the mansion house.[62]

|

|

The Echols’ have maintained the

house in excellent. Recently, the house was sold to James and JoAnne Athey, who

live adjacent to the property and have a family tie with the Echols. At the time

of this report, completion of the transfer of the house is

pending. |

| EXTANT FEATURES |

| Mansion |

| Building Evolutions |

| Phase I: Original Construction |

The floor plan of the earliest

portion of the house is approximately square in form (±20’-10” x ±20’-6”), with

the doorway entrance on the west elevation off-center towards the southwest

corner of the building. The building is two stories high, with one room on the

first floor and another room on the second floor. It is supposed that vertical

access to the loft was gained by use of a ladder in the northwest corner. The

home, which commands a view of the

The floor plan of the earliest

portion of the house is approximately square in form (±20’-10” x ±20’-6”), with

the doorway entrance on the west elevation off-center towards the southwest

corner of the building. The building is two stories high, with one room on the

first floor and another room on the second floor. It is supposed that vertical

access to the loft was gained by use of a ladder in the northwest corner. The

home, which commands a view of the |

|

One window retains its original,

wide muntins; while scratched into the glass of another window are the initials

TFM, presumably for Thomson Francis Mason who owned the house from 1897 to 1930

and lived there earlier in his youth. A large brick fireplace, recently rebuilt

of salvaged brick after the existing poorly fired salmon colored brick

deteriorated, is centered on the southern wall. Exposed second-floor joists were

hand-hewn. Tree pegs, sawn flush with the joists, suggest there had been

additional structural support down the center of the second floor perpendicular

to the joists. |

| Phase II: First Addition |

The first addition may have been

built to align with the west elevation of the original structure. Its dimensions

are roughly 24’-6” x 33’-5” x two stories tall. a cellar and an attic, which may

have sheltered household slaves[63],

add to the available space. The first addition may have been

built to align with the west elevation of the original structure. Its dimensions

are roughly 24’-6” x 33’-5” x two stories tall. a cellar and an attic, which may

have sheltered household slaves[63],

add to the available space. |

|

The woodwork in this addition is

of the Asher Benjamin style and may have been added during a ca. 1830s

remodeling.[64]

The stone firebox exhibits distress tooling conducive with an earlier applied

finish.[65] |

|

The first-floor joists are logs

dressed on two sides with bark retained on the undressed

portions. |

| Phase III: Second Addition |

The ca. 1819 second addition is

measures approximately 48’-6” x 33’4” with a 11’-2” deep porch on the east

facade and a 9’-6” deep porch on the west fascade. The addition stands 2-1/2

stories tall with a cellar. The ca. 1819 second addition is

measures approximately 48’-6” x 33’4” with a 11’-2” deep porch on the east

facade and a 9’-6” deep porch on the west fascade. The addition stands 2-1/2

stories tall with a cellar. |

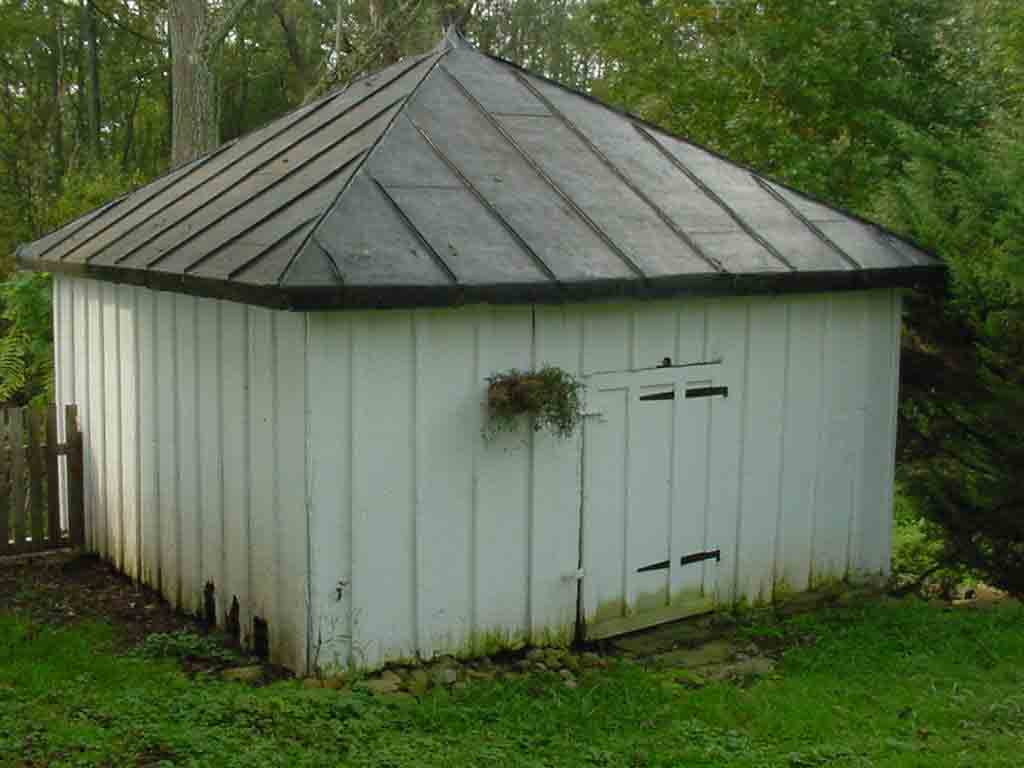

| Carriage House |

| The carriage house, which is purported to have later been a schoolhouse, measures approximately 40’-8” x 20’-6”. It is located within a yard of the original portion of the mansion house. Carriages could enter through the center of the structure prior to this area being enclosed. Stonework on the western elevation clearly shows the infill. |

| Dairy |

The dairy structure was

constructed of hand-hewn logs dressed on two faces. The structure measures

approximately 14’-5” square. The dairy structure was

constructed of hand-hewn logs dressed on two faces. The structure measures

approximately 14’-5” square. |

|

While this structure is known as

the smokehouse, its location near the steps to the spring and the construction

of its stone cellar built into the hillside, lend itself to cold storage

use. |

| Accessory Structure |

|

The accessory structure is of

relatively modern construction built of CMU blocks. Its dimensions are

approximately 30’-9” x 14’-6”. |

| Stable |

|

The stable is situated at the end

of a carriageway. Its dimensions are approximately 30’-6” x 18’-4”.

|

| Stone Stairway |

|

Stone stairs lead from between the

carriage house and the dairy down a slope to an early

road. |

| Early Road |

|

A stone wall borders an early

road, depicted on the 1834 survey of Samuel Clapham’s

land. |

| Spring |

|

A stone structure was built at the

head of a spring. The surrounding area downstream may have acted as an ice

pond. |

| Bank Barn |

|

A bank barn, which was not

accessible at time of survey due to pavement construction, exists to the

southeast of the mansion. |

| Shed |

|

An accessory structure, which was

also not accessible at time of survey, was identified the current owner as a

shed. |

| Machine Shed |

| A machine shed is situated

southeast of the mansion and currently houses farm

equipment. |

| Tenant House |

|

The appearance of a recently

remodeled tenant house, which may have been a slave quarter structure, changed

dramatically. The original construction was

balloon-framed timber. The building was considerably smaller than it is

today. |

| Cemetery |

|

The family cemetery dates back to

at least 1890. Several graves are located in the cemetery. It is currently

undergoing area brush and tree removal. A fence is scheduled to be erected

around the graveyard. |

|

The grave markers are all uncarved

except for one slab marking the grave of Sarah C. Chichester. The engraving

reads: |

| Landscape Terrace |

|

A landscape terrace was

constructed ca. 1819 on the east lawn of the mansion. The depth of the first terrace is greater

than the depth of the subsequent terrace levels. |

| Specimen Trees |

|

Several specimen trees, with

calipers greater than 48”, exist near the mansion house and along the early road

trace. |

| Well |

|

A well stands west of the first

addition. |

| NON-EXTANT FEATURES |

|

The 1834 survey plat shows

evidence of non-extant structures. One large structure appears to be depicted as

a round barn. A grouping of outbuildings may relate to slave quarters.

Archaeology would provide needed data to make these use

designations. |

| CONCLUSION |

|

Chestnut Hill is a Revolutionary

War era farm likely built by an English Baptist who emigrated from |

|

Archaeology at Chestnut Hill would

possibly yield information about the Native Americans who settled in the area.

Locations on hillocks overlooking a major waterway, such as at Chestnut Hill,

have been modeled as being potential Native American sites. Data for interpretation of the early

Baptist farmsteads, their dependencies, and slave quarters is also likely to be

found |

| ENDNOTES |

|

[1] Fairfax Harrison, “ Landmarks of Old Prince William

Volumes I and II,” Gateway Press, Inc., [2] Northern Neck Grant (NN) B, p. 166, Awbrey, Francis

grant of 745 acres, 18 December 1728, Land Office Patents & Grants/Northern

Neck Grants & Surveys, Library of Virginia. [3] NN D:50, Cocke, Catesby grant of 597 acres, 8 September

1731. [4] NN A:119, Albin, Thacker, and King grant of 460

acres, 20 January

1724. [5] NN F:82, Sinclair, Amos grant of 586 acres, undated and

unsigned in 1742. [6] NN A:118, Hawlin, William grant of 535 acres, 20

January 1724. [7] NN B:215, Hallin, Margaret grant of 416 acres, 12 March

1728/1729. [8] Peter Jefferson and Robert Brooks,”1737 Map of the

Northern Neck in Virginia in 4 parts and the 1747 Map of the Northern Neck in

Virginia in 6 parts”, Relic Room,

Prince William County Public Library. [9] NN I:277, Sinclair, John grant of 346 acres, 1 March

1776. [10] NN F:45, [11] Robert Baylor Semple, “ History of the Baptists in Virginia,”, Revised and Extended by G.W. Beale,

Church History Research and Archives, Lafayette, TN, 1976,

p.396. [12] [13] Loudoun Cemetery Database, Thomas Balch Library web

site, www.leesburgva.org [14] LN WB A:310, 13 May 1771. [15] Loudoun County Deed Book (LN DB) G:250, deed from

“ William Jones and Mary his wife” to Thomas George, 6 April

1770. [16] LN WB A:310, will of William Jones, 13 May

1771. [17] Internet sources [18] LN DB F:11, deed conveying 55 acres from James Steere,

cooper, and Abigail, his wife to William Jones, 17 March

1767. [19] Margaret Lail Hopkins, “ Index to The Tithables of

Loudoun County, Virginia and to Slaveholders and Slaves, 1758-1786,” Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc.,

[20] LN DB I:102, deed from Joshua Jones, tanner to David

Beaty and John Elliott, farmers, 22 November 1772. [21] LN DB A:212, 11 September

1758. [22] LN DB B:206, 10 August 1761, C:132 20 January 1762,

F:11 17 March 1767, G:246 9 April 1770. [23] LN WB A:310, will of William Jones, 13 May

1771. [24] Ibid. [25] LN DB M:36, deed from William Jones to Leonard

Ansell. [26] Loudoun Cemetery Database, Thomas Balch Library web

site, leesburgva.org, Margaret Fry died 10/12/1851; also Ancestry.com

RootsWeb.com posting by Harold F. Hahn whose gggggrandmother is Margaret Fry

transcribed gravestone “ SACRED To the memory of Margaret Fry, wife of John N.

Fry, Daughter of Leonard Ansil.” [27] LN DB G:250, Deed conveying 519 acres from William

Jones to Thomas George, 6 April 1770. [28] Ibid., Deed

states “ whereupon Thomas George now lives.” evidencing that George may have

built the house prior to purchasing the property. ALSO [29] Personal Interview with Don Swofford, Historical

Architect, DASA Architects, [30] LN WB F:198, probate inventory of Thomas George, 5

November 1798. [31] LN WB F:52, will of Thomas George, 8 October

1798. [32] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham, survey in oversize file, Loudoun County Court Archives, 14 April

1836. [33] LN DB N:13, deed conveying 200 acres from Thomas George

to Josias Clapham, 10 October 1779. [34] NN E:142, Clapham, Josias grant of 522 acres, 18 March

1739. [35] LN DB M:129, lease and release deeds conveying 150

acres from Anthony Haynes and Susannah, his wife to Josias Clapham, 12 May

1772. [36] LN DB T:257, deed conveyed furnace mountain tract from

Henry Lee to Josias Clapham, et.al., 14 January

1792. [37] [38] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham, Survey of Samuel

Clapham’s Land filed with & handed in with Com’s of [39] LN WB G:92, will of Josias Clapham, 12 September

1803. [40] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham, deposition of George Chichester, 9 March

1833. [41] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham, deposition of Joseph C. Hart, 22 April

1833. [42] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham, deposition of George Chichester, 9 March

1833. [43] LN Chancery case M205, John Barrett v. Samuel Clapham,

answer of Samuel Clapham, 4 April 1825. [44] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham’s administrators, deposition of George Chichester, 9 March

1833. [45] LN DB 3M:1, Samuel Clapham and Elizabeth, his wife

placed “ The Mansion House and farm on that the said Samuel Now resides called

Chestnut Hill containing Eight hundred Acres more of less” as loan collateral

with Thomson F. Mason and Richard Henderson, 28 March

1826. [46] LN DB 3M:1, Samuel and Elizabeth Clapham convey trust

to Richard C. Henderson and Thomson F. Mason, 28 March

1826. [47] CD510 Colonial Virginia Source Records, 1600s-1700s,

Index to [48] Eugene M. Scheel, “ Loudoun Discovered Communities,

Corners & Crossroads Volume Two, Leesburg and the Old Carolina Road,”

originally published in The Loudoun

Times-Mirror, Leesburg, Virginia, Updated and Expanded with Maps &

Photographs by The Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia,

2002, p. 41. [49] LN Chancery case M1567, Chatham Fire Insurance Co. v.

Samuel Clapham’s administrators, 1833. [50] John Vogt and T. William Kethley, Jr, “ Loudoun County

Marriages 1760-1850,” Iberian Publishing Company, Athens,

GA. [51] LN DB 4O:71, referenced deed from George Price to

Richard H. Henderson, unrecorded, 23 November 1833 [52] LN DB 4O:71, deed from George Price to Betsey Clapham

Price Mason, 16 October 1839. [53] [54] See Oral History

Interview with Alton Echols in

full report, a copy of which is at the Thomas Balch

Library. [55] [56] FX WB 3N:355, will of J. Francis Mason, 13 September

1897. [57] LN DB 7W:108, 6 October 1902; LN DB 8A:22, 6 February

1905; LN DB 8B:274, 16 December 1905; among others. [58] LN DB 10G:413, deed conveying Chestnut Hill by Wilber

C. Hall, special commissioner to Lucy J. Gore due to Hall vs. T. F. Mason suit

and subsequent foreclosure, 5 November 1930. See also Oral History Interview with Alton Echols

in full report, a copy of which is at the Thomas Balch

Library. [59] John G. Lewis,

“ Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Survey Form Chestnut Hill,” file number 53-69,

[60] Linda DeButts,

Loudoun Times-Mirror, article on auction of Chestnut Hill, June 25, 1987, p.

4. [61] LN DB 570:535, deed conveyed from executor of Lucy J.

Gore to Alton C. Echols, 28 March 1973. [62] DeButts. [63] Personal Interview with Don Swofford, Historical

Architect, DASA Architects, [64] Ibid. [65] Personal Interview with |