| Centreville, VA Civil War Fortifications | |||||||||||||||

|

by Debbie Robison | November 2003 STRATEGIC SIGNIFICANCE |

|

Time and again, it was proven; the heights of Centreville were strategically

significant during the sectional conflict of the Civil War. The ridge, on which

Centreville is situated, held a strategic and commanding view of the panorama

to the west. Approaches from the east were also within a viewshed visible from

the ridge. Union Brigadier-General Irvin McDowell summed up the tremendous

importance of holding the heights of Centreville: Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division For if he [the enemy] should once obtain possession of this ridge, which overlooks all the

country to the west of the foot of the spurs of the Union Major-General Geo. B. McClellan, after reviewing the

Confederate fortifications constructed in the winter of 1861/2, believed the

position to be formidable. From this it will be seen that the

positions selected by the enemy at Centreville and Manassas were naturally very

strong, with impassable streams, and broken ground, affording ample protection

for their flanks, and that strong lines of intrenchments swept all the

available approaches…That an assault of the enemy’s position in front of

Washington, with the new troops composing the Army of the Potomac, during the

winter of 1861-’62, would have resulted in defeat and demoralization, was too

probable…[2] The Centreville fortifications were used to cover the retreats of

the Union army after both battles of First and Second I shall to-morrow

attempt to gain the heights of Centreville by crossing at the lower fords of It is hoped we are

sufficiently far ahead to enable the seizure of the Centreville Heights in

advance of the enemy, but if the movement is detected our flank and rear may be

attacked…General Newton, First Corps, will move from Bristoe through Manassas

Junction,…thence to Centreville, by way of Mitchell’s Ford, seizing and holding

the heights and redoubts. General Sedgwick…to the heights on the right of

Centreville, looking toward Warrenton… The Reserve Artillery…to the rear of

Centreville…Such additional batteries as may be required for the heights of

Centreville will be placed in position… - S Williams, Assistant Adjunct General.[4] General R.E. Lee considered attacking Union troops at Centreville

in order to drive them back to their fortifications around I do not, however, think it advantageous

to attack him in his entrenchments, nor do I see any benefit derived from

pursuing him further…[5] For the balance of the war, Union troops held Centreville as a

crucial link in the chain of defenses surrounding and protecting FORTIFICATION CONSTRUCTION |

| Confederate and Confederate

Entrenchments – June and July 1861 |

| The Confederates

were first to construct some entrenchments at Centreville in 1861. Brig. Gen.

Bonham took an advance position at Centreville in June 1861, but the

Confederates retreated to No enemy appeared at Centreville…he

having abandoned his intrenchments [sic] the night before…– I.

B. Richardson, Colonel, Commanding Fourth Brigade, First Division [Union][7] Union Defenses - Preparation for First Bull Run, July 1861 |

| Union Brigadier-General

Irvin McDowell, having become acquainted with the terrain, described the area

as follows: Centreville is a village of a few houses,

mostly on the west side of a ridge running nearly north and south. The road

from Centreville to McDowell felt vulnerable to a flank attack, should the enemy cross

Bull Run at Blenker’s brigade took position at Centreville, and commenced throwing up intrenchments –

one regiment being located at the former work of the enemy, one to the west of

the town on the Warrenton road, and two on the heights towards Bull Run… - D.

S. Miles, Colonel Second Infantry, Commanding Fifth Division [Union][10] Colonel Miles, on whose staff Prime was attached, examined a

battery on the road from Fairfax Court-House; after which, the pioneers of the

Garibaldi Guard were ordered to construct a redoubt with two embrasures, so as to sweep the old Braddock road so

that Confederate troops could not outflank them from …the brigade advanced from the camp and

took up their assigned position on the heights of Centreville east of

Centreville about daybreak: the Eighth Regiment New York State volunteers…on

the left of the road leading from Centreville to Fairfax court House; the

Twenty-ninth Regiment New York State Volunteers…on the right of the same road,

both fronting towards the east; The Garibaldi Guard…formed a right angle with

the Twenty-ninth Regiment, fronting on the south…three pieces left in

Centreville were placed near the right wing of the Twenty-ninth Regiment; three

others on the left wing of the Eighth Regiment, where intrenchments were thrown

up by the pioneers attached to the brigade…[12] Confederate

Fortifications – Winter Encampment, October 1861 to March 1862 |

|

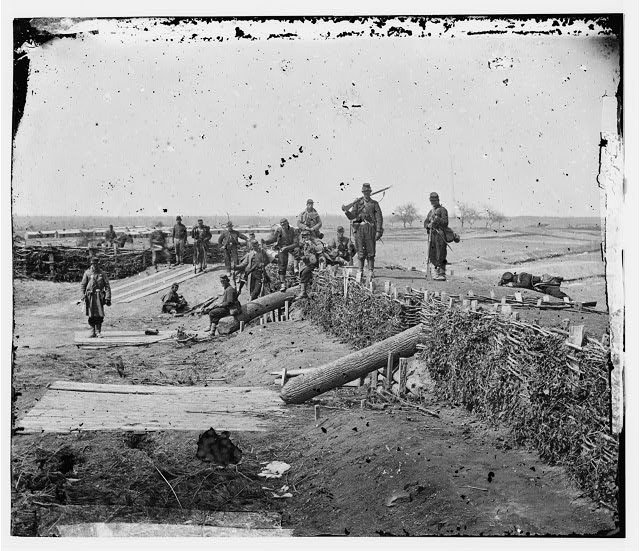

Principal Fort at Centreville, 1862, | Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division Late in the evening of October 16, 1861, General Joseph Eggleston

Johnston’s army arrived in Centreville and soon began construction of forts,

breastworks, riflepits, and batteries on the high ground and at strategic

locations. A sketch map drawn in December of 1861 depicts the location of the fortifications

and troop encampments. George Wise, of the Seventeenth Virginia Infantry, recollected the

construction of fortifications by the Confederates. …the Army of Northern Virginia soon made

Centreville what On March 14, 1862, Lieutenant McAlester, U. S. Engineers, surveyed

and described the recently deserted Confederate fortifications at Centreville.

A reconnaissance of the works at Centreville, made by Lieutenant McAlester, | New Union Defenses - August 1862 and September 1863 |

| Private Robert Knox Sneden wrote in his diary on August 30, 1862,

during the second Battle of Bull Run, that Union troops were establishing new

defenses at the old forts at Centreville. Lanterns were seen moving all night on

the old Rebel forts at Centreville, while the sound of hundreds of axes were

heard on all sides. Our engineers were putting Centreville in a state of

defense, pulling down houses and mounting guns.[15] [1] Official Records of the Civil War (OR), Series I, Vol 2, 04 Aug 1861, p. 317 [2] OR, Series 1, Vol. 5, 00 March 1862, p. 54. [3] OR, Series 1, Vol 29, Pt. II, 16 Oct 1863, p. 306. [4] Ibid., p. 304. [5] OR Series 1, Vol 29, Pt. I, 16 Oct 1863. [6] OR, Series I, Vol 2, 02 Jun 1861, p. 62. [7] OR, Series I, Vol 2, 19 Jul 1861, p. 313. [8] OR, Series I, Vol 2, 04 Aug 1861, p. 317. [9] Ibid. [10] OR, Series I, Vol 2, 24 Jul 1861,p. 423. [11] OR, Series I, Vol 2, 01 Aug 1861, p. 334. [12] OR, Series I, Vol 2, 04 Aug 1861, p.427. [13] [14] OR Series 1, Vol. 5, 00 March 1862, p. 54. [15] Robert

Knox Sneden, Eye of the Storm, Simon and |